Output and Income for Australian construction firms

Australian industry data is provided in the Australian Bureau of Statistics annual publication Australian Industry (ABS 8155), produced using a combination of the annual Economic Activity Survey and Business Activity Statement data provided by businesses to the Australian Taxation Office. The data includes all operating business entities and government owned or controlled Public Non-Financial Corporations. Australian Industry excludes the finance industry and public sector, but includes non-profits in industries like health and education and government businesses providing water, sewerage and drainage services. The selected industries included account for around two-thirds of GDP. Excluded are ANZSIC Subdivisions 62 Finance, 63 Insurance and superannuation funds, 64 Auxiliary finance and insurance services, 75 Public administration, and 76 Defence. The most recent issue is for 2018-19.

The analysis is based on industry value added (IVA) and industry employment. IVA is the estimate of an industry’s output and its contribution to gross domestic product (GDP), and is broadly the difference between the industry’s total income and total expenses. IVA is given in current dollars in Australian Industry. The data is presented at varying levels for industry divisions, subdivisions and classes, but unfortunately does not include the number of firms. There is, however, some firm size data. Micro firms have less than 5 employees, small firms 3-19, medium firms 20-199 and large firms more than 200 employees.

Figure 1 shows large construction firms have 15% of employment, 30% of wages and salaries and 23% of output. Medium firms have 18% of employment, 27% of wages and salaries and 21% of output, and micro and small firms account for approximately 65% of employment but only 55% of output. The labour-intensive work of small firms largely explains the lack of long-run growth of productivity in construction.

Figure 2 shows large firms have twice the level of output and income per employee compared to small and micro firms, and medium firms nearly 50% more. There is no significant difference between micro and small firms. IVA per employee is an imperfect but useful proxy for productivity, and this shows the gap between large and medium size firms is significant.

The relationship between firm size and IVA per employee is not surprising, large firms are typically better managed than small firms. Management is the most important determinant of the capacity and capability of construction firms, because managerial skills give a contractor greater flexibility. How firms utilise their capabilities differentiates them within a diverse, location-based production system. It is widely recognised there are differences between industries in the way that production is organized and new technology adopted, adapted and applied, but differences within industries generally get less attention. Important differences are the individual characteristics of firms such as their size, the effects of competitive dynamics, and how the adoption of new technology by one company in an industry influences the adoption of technology by other companies in that industry. For building and construction this is significant, not only because of the number of small and medium size firms, but because of the size and reach of the major firms.

Figures 3 and 4 show IVA and income per employee for three years respectively. The most recent 2018-19 year is representative of the industry, based on this data. Construction firms convert around a third of their income per employee into IVA per employee, however large firms have twice the income per employee. These figures identify the balance sheet effect, as firms leverage the capital on their balance sheet to maximise revenue and profits.

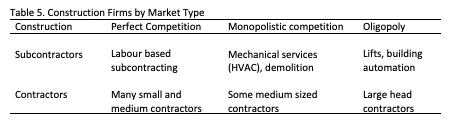

Construction has a large number of small firms bidding for work in local markets with little or no control over prices. There is a diminishing number of firms that can deliver large projects in a given region or have national operations, and there are a few dozen multinational corporations in construction. Construction economics has a wide range of views on the types of markets these firms operate in and their competitive behavour. There is, however, universal agreement that construction is an industry of projects, and firms operate in markets for projects of many different types.

The relationship between firm size and contract value is therefore a fundamental reality in construction, and is also the foundation of the relationship between projects and firms. A firm is a legal entity and the typical reporting period is one year. A firm’s income is the cumulative cash flow of their portfolio of projects over a year. The focus on projects and construction management in construction research obscures the role of firms as the ongoing participants in the industry.

For firms in construction markets annual revenue is the aggregated income from current work, or contracts won but not completed. Construction firms and contracts range widely in duration, size and value, but the amount of work a firm can take on must be related to the capital a firm has available. This relationship between firm size and the annual value of contracts or projects undertaken is based on the assumption that construction firms seek to maximize revenue but are constrained by their working capital. In construction the contract packages reflect the complexity of work, so there is a wide range of contract sizes. Construction contracts can, therefore, be arranged based on contract size and complexity. This is a well-known and widely agreed characteristic of the industry, with the relationship first researched in the 1980s. Competing contractors’ bids were affected by the type of project and by the value range, small firms considered both contract type and size, and large firms were more successful when bidding for large contracts. Contract size and complexity are also important because the wide range of contract sizes in the construction market is the major determinant of the number of firms. In a project-based market, defined by project size and complexity, there are many standardized projects but few companies able to undertake particularly difficult projects, those large construction firms deliver large projects and/or with a high degree of complexity.