Australian Construction Productivity at the Industry Level

The rate of growth of productivity in the construction industry in a number of countries has lagged that of other industries for at least five decades, and the earliest studies that identified this problem date from the late 1960s. Two explanations for the lack of demonstrable improvement in construction productivity are possible. The first is the importance of measurement, data and issues about the structure and use of price indices for estimating real output (i.e. adjusted for inflation).

The second is the nature of the product and the methods used in delivering and managing the processes involved. Construction is a labour intensive industry in comparison with manufacturing, but there has been a significant increase in the prefabricated component of construction, which could have been expected to lead to productivity growth. Also, construction methods have become more capital intensive as machinery has got heavier, and the number of cranes, powered hand tools and other equipment used has increased. However the productivity growth that one would expect to observe as a result of these trends has not occurred, according to measurements by national statistical agencies.

Productivity estimates require both a measure of labour inputs, such as hours worked or people employed, and a measure of output, called Industry value added (IVA, the difference between total revenue and total costs). IVA is then adjusted for changes in prices of materials and labour to estimate Gross value added (GVA) using price indexes that assume there has been no change in the quality of buildings. Another problem is the application of a single deflator to the diverse range of buildings and structures. This inability to capture functional differences and quality changes in buildings and structures has adversely affected the measurement of productivity, if construction value added is underestimated due to the deflators used, construction productivity has also been understated.

This post compares the deflated GVA per person employed to the IVA per person employed for Building, Engineering and Construction services (the trades), and Total construction. The GVA data comes from the ABS National Accounts (chain volume measures of economic activity). The IVA data and number of people employed in June each year comes from ABS Australian Industry.

A Proxy for Construction Productivity

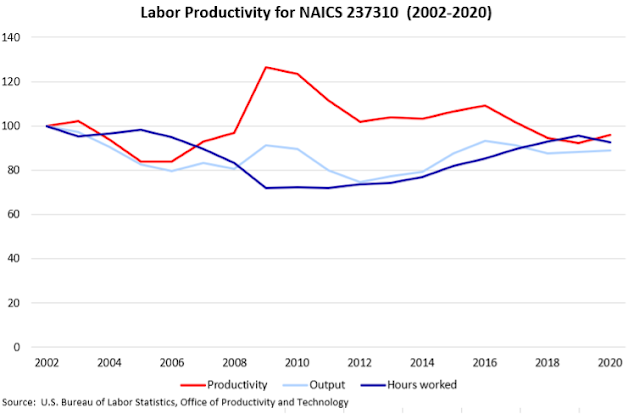

In Figure 1 industry output is in constant dollars (the deflated value adjusted for price changes). GVA is the quantity of output produced in a year. The employment data includes all workers but not whether they are full or part-time, or hours worked.

Figure 1. Construction Productivity by Industry

Source: ABS, CER

As a measure of productivity GVA per person employed is very approximate, typically the number of hours worked would be used for employment and June may not be a representative month for employment in many industries. Nevertheless, this graph looks familiar, with flatlining growth in Total construction productivity over the period, despite a few bumps along the way. It appears to be a useful productivity proxy.

Using the same data, GVA per person employed can be found for Building, Engineering and Construction services. Here a slight decline in Building has been offset by a small rise in Construction services output per person, with the effects of the pandemic on both apparent in the decline over 2020-21. Building construction may have been affected by a shift from commercial to an increased share of residential in the output mix and more high rise work. Because Construction services are generally labour intensive they will have a lower value of output per person, but this data shows there was increase in this measure of productivity between 2007 and 2021 and Construction services was the only one of the three industries to register a gain on this measure.

Engineering construction activity took off in the mining boom from 2010, and output per person has followed the rise and fall in work done since and, although below the peak years of 2012-14, it now reflects the large volume of infrastructure work in transport and energy. Since 2011 GVA per person in Engineering has been much higher than Building construction, nearly twice as much in some years, and Construction services, nearly three times as much in some years.

These differences in output per person employed reflect differences in capital requirements and expenditure on purchases of buildings, structures, software, equipment and machinery (known as gross fixed capital formation or GFCF). The higher the capital requirements, or capital intensity, of an industry the higher the level of output per person employed is expected to be, because workers with more capital are more productive. Both excavators and shovels require one operator but the former shifts more soil.

Current Dollar Industry Comparison

The chain volume measure of GVA per person employed can be compared to the original, unadjusted current dollar Industry value added (IVA) per person employed. Again, this is an indicative but imprecise proxy for construction productivity. In Figure 2 there is a clear upward trend in all three industries, with increasing nominal value of output as prices rise faster than the number of people employed.

The growth in IVA per employee for Building is the greatest contrast to the GVA data. Here, Building has had a sustained increase since 2012 compared to the flat, no growth trend in GVA per employee. This suggests there has been a better productivity performance by building contractors than the one recorded in official statistics.

Engineering has a similar pattern in both GVA and IVA graphs, with a sharp rise in output per employee after 2010 that flattened out after 2016 at around 50 per cent higher than the pre-mining boom level. This has been a significant increase in productivity. Both Building and Engineering typically have larger firms than found in Construction services, which has lagged the other two industries in growth in IVA per employee.

Without deflation the value of output could be expected to rise somewhere around the rate of CPI inflation, which totalled 35.8 per cent and averaged 2.2 per cent a year between 2007 and 2021. Over that period Building IVA increased by 120 per cent, Engineering IVA by 117 per cent, and Construction services by 50 per cent. More significantly, IVA per person employed for Building increased by 61.6 per cent, for Engineering by 57.3 per cent, but for Construction services only 27.7 percent, suggesting that is where the productivity ‘problem’ lies. However, the IVA and GVA figures are contradictory, with the latter showing better performance.

Figure 2. Nominal output per employee

Source: ABS, CER

IVA per employee again highlights differences in the capital requirements of industries. In the long run, investment in GFCF determines industry growth rates and their level of labour productivity. Labour intensive industries like Construction services have a low level of IVA per person employed, but also have lower capital requirements. Engineering has always been more capital intensive than Building, but the gap seems to have closed with the increase in residential high-rise activity after 2016.

Conclusion

Construction productivity estimates are usually given for Total construction, and typically show little or no growth over many decades. However, Total construction is measure of the combined performance of three different industries: Building, Engineering and Construction services. This post compared the deflated GVA per person employed to the nominal IVA per person employed for Building, Engineering and Construction services (the trades), and Total construction.

The deflated GVA per person employed data is a proxy for productivity because the value of output is adjusted for price changes, As a combination of deflated output and employment GVA per person employed looks like a measure of productivity, but while it is indicative that is not really the case. Although similar to the output and input data needed to calculate productivity, indexes of output and input are used for productivity analysis, not the original data, and hours worked not numbers employed used.

When the mostly flat chain volume measures of GVA per person employed are compared to the current dollar IVA per person employed there is a clear upward trend in IVA all three industries, with increasing nominal value of output as prices rise faster than the number of people employed. IVA per person in Building and Engineering has increased at nearly twice the rate of CPI inflation, but Construction services by less since 2007.

Construction services IVA per person employed grew significantly less than Building and Engineering. However, the GVA per person employed performance was much better, the only one of the three industries to register a gain on this measure. Construction services have a large impact on productivity because they account for 60 per cent or more of Construction output.

The usefulness of both GVA and IVA per person employed as a proxy for productivity per person is limited, but indicative. In both cases the difference in capital intensity appears to be the determining factor in the level of productivity (measured as dollars per person employed), and the increase in apartment building would explain the rapid rise in Building IVA per person employed. The effect of changes in output (the mix of buildings and structures delivered) will be explored in another post. Why that increase in Building IVA per person employed was not picked up in the GVA per person employed estimates is also an interesting question.