Technological Change and Constructing the Built Environment

I was once attacked by a colleague for, as he put it, ‘not considering the great mass of people employed in construction’. We were working for a government inquiry into collusive tendering and discussing recommendations to improve productivity and efficiency in the final report. At the time there were significant changes affecting the Australian industry that had far more impact than the legislative and regulatory reforms the inquiry led to. The industrial relations system was moving from a centralised award based one to a more decentralised system with enterprise bargaining and site agreements. International contractors were entering the market and the larger engineering and architecture practices consolidating. As the industry began to recover from a speculative office building bubble and the economy rebounded from a deep recession, construction employment increased and continued to grow for the next few decades. Construction as used here refers to all the firms and organizations involved in design, construction, repair and maintenance of the built environment.

Where these longer run trends were going was not obvious at the time. There have been significant changes in the range of activities and types of firms involved in construction of the built environment over the last few decades. Two trends underpinning those changes were the increasing use of multi-disciplinary project teams as the boundaries between professional disciplines became less distinct, and the inhouse versus outsourced decision about provision more common. Facilities management is an example, an activity that used to be done internally but is now often outsourced, sometimes but not always to construction contractors. Consultants bid for work as contractors, and contractors do consultancy and project management. Urban planning was once primarily associated with design, but is now linked to real estate and development. The process of structural change in industry occurs as technology, institutional and firm capabilities develop and change over decades.

When considering the relationship between construction of the built environment and technological change the past is really the only guide available, so the starting point for this discussion is the first industrial revolution in England at the beginning of the nineteenth century when modern construction and its distinctive culture began to form, followed by the twentieth century’s attempts to industrialise construction. This history is important because, after more than 200 years of development, construction of the built environment happens today within an established system of production based on a complex framework of rules, regulations, institutions, traditions and habits that have evolved over this long period of time.

But how useful is history and how can it be used? Are there appropriate historical examples or cases to study to see if there are lessons relevant to the present? The answers depend to a large extent on context, because a key characteristic of the history of technology is the importance of institutions and the political and social context of economic outcomes. Also, understanding how policies were developed in the past and how effective they were requires understanding the changing context of policy implementation. However, as economist Paul Samuelson pointed out ‘history doesn't tell its own story and ‘conjectures based on theory and testing against data’ are needed to uncover it. Drawing the right lessons from history is a nuanced exercise.

Over time industries and products evolve and develop as their underlying knowledge base and technological capabilities increase. The starting point for a cycle of development is typically a major new invention, something that is significant enough to lead to fundamental changes in demand (the function, type and number of buildings), design (the opportunities new materials offer), or delivery (through project management). Major inventions give a ‘technological shock’ to an existing system of production, which leads to a transition period where incumbent firms have to adjust to the new business environment and new entrants appear to take advantage of the new technology. Economist Joseph Schumpeter called this process creative destruction, and it leads to the restructuring and eventually consolidation of industries. That is what happened to construction and related suppliers of professional services, materials and components after the first industrial revolution.

The drivers of development for industries in the twenty-first century are emerging technologies such as augmented reality, nanotechnology, machine intelligence, digital fabrication, robotics, automation, exoskeletons and possibly human augmentation. Collectively, these digital technologies are described as a fourth industrial revolution, and their capabilities can be expected to significantly improve as new applications and programs emerge with the development of intelligent machines trained in specific tasks. Innovation and technological change is pushing against what are now long-established customs and practices of the industries in the diverse value chain that designs and delivers the projects that become the built environment.

How technological change affects these industries differs from more widely studied industries like computers, automobiles or aerospace because of the number and diversity of firms involved in designing, constructing and managing the built environment. With the range of separate industries these firms come from, construction of the built environment is the output of a broad industrial sector made up of over a dozen individual industries. Not an ‘industry’ narrowly defined, but a broad industrial sector that is organised into a system of production with distinctive characteristics. A second difference is the age of these industries, many of which are mature industries in late stages of their life cycle. These differences create a different context for questions about industry, innovation and technological change, about how firms compete and how the system of production is organised as fourth industrial revolution technologies like digital twins and drones spread through construction and the pace of digitization increases.

As well as the contractors, subcontractors and suppliers for new builds, there are also many firms and people mainly engaged in the alteration, repair and maintenance of the built environment. The broad base of small firms is a distinctive feature of construction, and these family-owned firms engaged in repair and maintenance work will largely continue to use the materials and processes they are familiar with. Old technologies can survive long after the innovations that eventually replace them arrived, such as the telegraph, fax machine and vinyl records with telephones, email and CDs. Stone, tile, brick and wood have been widely used materials for millennia, and industrialized materials like corrugated iron and concrete are ubiquitous. For maintaining and repairing the existing stock of buildings and structures, many of the skills, technologies and materials found today will continue to be used far into the future. That does not mean firms mainly involved in repair and maintenance will not be affected in some way by the fourth industrial revolution.

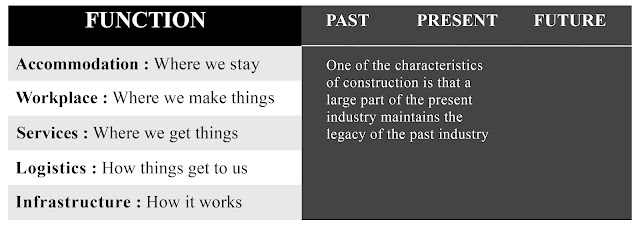

Figure 2.

Construction of the built environment has characteristic organizational and institutional features because it is project-based with complex professional and contractual relationships. How firms utilise technology and develop technological capabilities differentiates them within this location-based system of production. Emerging technologies in design, fabrication and control have the potential to transform construction over the next few decades, possibly less, and the book suggests firms will follow low, medium or high-tech technological trajectories, determined by their investment in the emerging technologies of the fourth industrial revolution.

A broad view of what future construction might look like is based on successful solutions being found for the many institutional and technical problems involved in transferring fourth industrial revolution technologies to construction. Without downplaying the difficulty of those problems, similar challenges have been met in the past, but those solutions led in turn to a reorganization of the system of production.

There are very many possible futures that could unfold over the next few decades as technologies like artificial intelligence (AI), automation and robotics develop. However, the key technology underpinning these further developments is intelligent machines operating in a connected but parallel digital world with varying degrees of autonomy. These are machines that have been trained to use data in specific but limited ways, turning data into information to interact with each other and work with humans. The tools, techniques and data sets needed for machine learning are becoming more accessible for experiment and model building, and new products like generative design for buildings plans, drone monitoring of onsite work and 3D concrete printers are available.

Intelligent machines are moving from controlled environments, like car manufacturing or social media, to unpredictable environments, like driving a truck. In many cases, like remote trucks and trains on mining sites, the operations are run as a partnership between humans and machines. There are also autonomous machines like autopilots in aircraft and the Mars rovers. As well as rapid development of machine intelligence, technological change in the form of new materials, new production processes and organizational systems is also happening. Sensors and scanners are widely used, 3D concrete printing is no longer experimental, cloud-based digital twins are available as a service, and online platforms coordinate design, manufacture and delivery of building components using digital twins.

A period of restructuring of construction occurred in the second half of the 1800s when the new industrial materials of glass, steel and reinforced concrete arrived, bringing with them new business models, new entrants and an expanded range of possibilities. The development of modern construction was not, however, a smooth upward path of progress and betterment. It went in fits and starts as new inventions and innovations arrived, slowly then quickly, often against critics of the modern system of production and workers, fearing technological unemployment and lack of government support during a time of technological transition, who resisted new technology and sometimes sabotaged equipment. The issue in the past, like today, was in fact not the availability of jobs but the quality of skills during the diffusion of new technologies through industry.

The only previous comparable period of disruptive technological change in construction of the built environment is the second half of the nineteenth century. Between 1850 and 1900 construction saw the rise of large, international contractors, who reorganized project management and delivery around steam powered machinery and equipment. In particular, the disruptive new technologies of steel, glass and concrete, which came together in the last decades of the century, led to fundamental changes in both processes and products. If that is any guide, we can expect technological changes to operate today over the same three areas of industrialization of production, mechanization of work, and organization of projects that they did then. And today, just as in 1820 when no-one knew how different construction would be and what industry would look like in 1900, we can’t see construction in 2100. That is a long way out, and we can only guess at the level of future technology. We can, however, use what we already know from both history and the present to form a view of what is possible over the next few decades based on what is currently understood to be technologically feasible.

It should be clear that the role of fourth industrial revolution technologies will be to augment human labour in construction of the built environment, not replace it. Generative design software does not replace architects or engineers. Optimization of logistics or maintenance by AI does not replace mechanics. Onsite construction is a project-based activity using standardized components to deliver a specific building or structure in a specific location. The nature of a construction site means automated machinery and equipment will have to be constantly monitored and managed by people, with many of their current skills still relevant but applied in a different way. Nevertheless, in the various forms that building information models, digital twins, AI, 3D printing, digital fabrication and procurement platforms take on their way to the construction site, they will become central to many of the tasks and activities involved. Education and training pathways and industry policies with incentives for labour-friendly technology will be needed.

Figure 3.

Because construction involves so many firms and people the technology driven changes discussed here will have significant and profound economic and social consequences. This would be a good opportunity for government and industry to work together to develop policies and roadmaps for those firms, and to support ‘the great mass of people’ employed in construction of the built environment who will be affected by them. The future is not determined, although technological change and creative destruction continue to reshape and restructure industry and the economy, decisions made today create the future.