Changes in software capital expenditure and the capital stock

Industry investment in physical and intellectual assets is essential for building capacity and upgrading technology, and one reason for the low rate of productivity growth of Australian industry is the lack of business investment in the capital stock, which is the accumulated amount of machinery, equipment, buildings, structures, software and R&D in the economy. With investment the capital stock is upgraded and grows, and a low level of investment means slower growth in output, increasing economic inefficiency, less economic dynamism, and lower productivity.

Productivity is determined by the amount and quality of capital per worker, their skills and experience, and the rate of adoption of new technology. This post looks at the 2023-24 data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics for productivity, capital stock [1], and gross fixed capital formation (GFCF, i.e. capital expenditure or capex) on computer software. Because the ABS data on machinery and equipment (M&E) capital stock and GFCF includes investment in computers and information technology with all other M&E, the software data is one way of tracking the digitisation of Australian industry.

Software and Labour Productivity

In 1987 Robert Solow made his well-known observation ‘You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics‘, often referred to as the Solow paradox. Explanations for the paradox included measurement issues, the relatively small share of information technology (IT) in total investment, the time needed for industry to reorganise around IT, a substitution effect as computers made other capital like machinery and transport equipment more efficient, localised gains in IT manufacturing, that hard to measure service industries like finance and professional services were major adopters of IT, and the alignment of computers with bureaucracy as they created more but not always more useful work (like email chains, online forms and time wasted browsing the internet).

Figure 1 shows Australia’s software net capital stock chain volume measure for All Industries (the capital stock adjusted for depreciation and changes in prices), and the hours worked labour productivity measure for the 16 market sector industries. Up to 2021 they had similar paths as both increased at about the same rate, but over the last three years the software capital stock has grown rapidly, and much more than labour productivity, which returned to trend after the spike during COVID. There is an echo here of the late 1990s, when software capex and the capital stock increased during the early stages of the IT revolution and the internet but the rate of growth of productivity did not increase, and in fact fell in the years around 2000.

Figure 1. Software capital stock and productivity

Source: ABS 5204 and 5260

Note: All Industries net capital stock chain volume measure, and hours worked labour productivity.

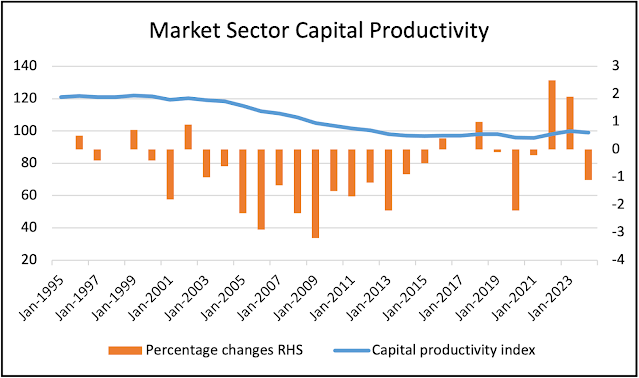

There is no suggestion of causality here, with the post-2021 increase in software capital stock not reflected (yet) in the productivity index. This is different to the M&E relationship with labour productivity in Figure 2 below (from the previous post), where productivity rose with a two year lag after the increase in the M&E capital stock that began in 2006, then flattened out after M&E stopped rising in 2015, and rose again a couple of years after M&E increased in 2021. There are several reasons why the M&E capital stock has a more direct relationship with productivity: new M&E typically replaces older but similar M&E, so does not require a lot of training or reorganisation, and is unlikely to be underutilised; new M&E will usually be smarter and more automated, so increases output but requires less labour; small firms have access to the same new M&E as large firms; and diagnostic software in new M&E makes maintenance easier with less downtime.

Figure 2. Machinery and equipment capital stock and productivity

Source: ABS 5204 and 5260

Note: All Industries net capital stock chain volume measure, and hours worked labour productivity.

The differences between software and M&E are important, and explain why there is a weaker relationship between the software capital stock and productivity. First is the training and learning required with new software, particularly for large complex systems, and the time it takes to become familiar with a new system or major update. Second, underutilisation is an issue because there are often features in a software system that are not used, but have to be paid for. Third is the implementation challenge, because software and IT investments will often be disruptive and many have been expensive failures. Finally, to take full advantage of new systems will typically require reorganisation, with redesigned processes and restructured roles. Small firms find all these factors more challenging than large firms with more resources and deeper skill sets, and the weak relationship between software capex and productivity growth may be because of the large number of small firms. As an aside, these were the explanations given for the productivity slowdown around 2000, and now they will apply again in the adoption of AI by businesses [2].

The lack of a relationship between the software capital stock and labour productivity becomes more apparent when comparing their growth for different industries over 2020 to 2024. As Table 1 shows, a couple high productivity growth industries like Agriculture and Accommodation also had large software capital stock increases, but then so did negative productivity growth industries like Manufacturing and Retail trade. In a group of five industries with capital stock increases between 80% and 90%, the labour productivity growth varied from -20% for Mining to +5% for both Wholesale trade and Administrative and support services. For both productivity and capital stock changes, the aggregate outcome balances out a wide range of outcomes across industries.

Table 1. Software net capital stock and productivity by industry 2020-2024

Software Capital Stock and Capex

The top two industries in Figure 3 are Professional, scientific and technical services, and Finance and insurance services, and they accounted for 43% of total software net capital stock in 2024, showing how concentrated it is in Australia, and those two industries are 7.6% and 7.8% of industry gross value added respectively. These are service industries that have output measurement issues because they are not goods producing, which is part of the reason for the weak IT/productivity relationship. Adding Information, media and telecommunications, and Public administration and safety make up the top four industries with 51% total software net capital stock and 23.4% of industry gross value added. Also service industries.

Figure 3. Software capital stock by industry

Source: ABS 5204.

Software capex is also concentrated in the same four industries, and they accounted for 49% of the total in 2024. Professional, scientific and technical services, and Finance and insurance services were again by far the largest. They are followed by Information, media and telecommunications and Public administration and safety. The next four industries had between $2 and $2.5 billion software capex and accounted for another 22% of total software capex. These were Electricity, gas, water and waste, Health care and social assistance, Retail trade, and Transport, postal and warehousing. Those eight industries did 71% of software capex and are 43.7% of industry gross value added.

The middle group of five industries of Construction, Education and training, Administrative and support services, Manufacturing, and Wholesale trade had 19% of capex and 18% of software capital stock in 2023-24. These industries are 25.5% of industry gross value added.

The bottom five industries are Agriculture, forestry and fishing, Accommodation and food, Mining, Arts and recreation, Rental, hiring and real estate services, had 7% of software capex and capital stock in 2023-24. These industries make up 19.3% of industry gross value added, of which Mining is 10.4%.

Figure 4. Software capital expenditure by industry

Source: ABS 5204.

Tracking Digitisation with the Software Capital Stock

The ABS does not separate capex for computers and IT from the M&E total, so the digitisation of Australian industry cannot be tracked through the M&E data. However, there is the data for computer software that was used above, and that provides an alternative method of tracking digitisation, because investment in computing equipment will also require expenditure on software to make it run.

Figures 5 and 6 have the percent change in the annual chain volume measure of the software net capital stock for each industry over five year intervals since 2000. This shows how annual capex, which varies considerably from year-to-year, accumulates over time into capital stock, and comparing the change in the capital stock in the five periods is indicative of the digitisation of Australian industry in three ways.

First, twelve of the 18 industries had their biggest increase in their software capital stock in the most recent 2019-2024 period, and for those industries this was the biggest percentage change in any of the five periods. Three other industries were close to their previous peak change, that was in the 2000-2004 period. The substantial increase in the software capital stock between 2000 and 2024 suggests an increase in the digitisation of industry.

Second, for nine industries the change in their software capital stock in 2015-2019 was lower than the previous 2010-2014 period, and in another five was similar. This suggests there had been a trend of falling software capex in many industries that was reversed in the most recent period of 2020-2024.

Third, between 2020 and 2024 seven industries increased their capital stock by over 100%, and seven between 75 and 99%. This level of software investment across so many industries is unprecedented in Australia. For example, in 2000-2004 Mining and Professional services both increased their software capital stock by over 100%, and in 2010-2014 Retail trade by 95%, but there has not been a software investment surge in the past comparable to the one in 2020-2024.

Figure 5. Software capital stock increase by industry over five year periods

Source: ABS 5204. Annual chain volume measure of net capital stock.

Figure 6. Software capital stock increase by industry over five year periods

Source: ABS 5204. Annual chain volume measure of net capital stock.

Out of the four software-intensive industries, Professional, scientific and technical services, Finance and insurance services, and Public administration and safety all had larger capital stock increases in 2020-2024 over 2015-2019, but for Information, media and telecommunications the increase fell to half the earlier rate of change. The 150% increase for Professional services was the second largest out of all industries, behind Retail trade (where increased online shopping will have been a driver of software capex).

Conclusion

Australian industry has greatly increased investment in computer software in recent years. Fifteen out of eighteen industries had or were close to record levels of capital expenditure on software for the five years 2020-2024, and seven of those industries increased their software capital stock by over 100%. This is a useful indicator of the increasing digitisation of industry, because the previous period of peak capex was 2000-2004, and that was followed by a decade and a half of lower capex for most industries.

However, software capex and capital stock is highly concentrated in Australia. Two industries, Professional, scientific and technical services, and Finance and insurance services, accounted for 43% of total software net capital stock in 2024, and 34% of capex. Those two industries are 7.6% and 7.8% of industry gross value added respectively. With Information, media and telecommunications, and Public administration and safety, the top four industries have 51% total software net capital stock, 49% of capex, and 23.4% of industry gross value added. However, of those four industries, only Professional services with 150% had a large increase in capital stock in 2000-2024, Information, media and telecommunications increased by only 24% and the other two by around 60%.

The next four industries were Electricity, gas, water and waste, Health care and social assistance, Retail trade, and Transport, postal and warehousing. Those accounted for another 22% of total software capex, 21% of capital stock, and almost 20% of industry gross value added. The largest increase in 2020-2024 capital stock was 190% by Retail trade, as increased online shopping drove software capex, and Health care had a 140% increase.

A group of five industries of Construction, Education and training, Administrative and support services, Manufacturing, and Wholesale trade, had 19% of capex and 18% of software capital stock in 2023-24. These industries are 25.5% of industry gross value added.

The bottom five industries of Agriculture, forestry and fishing, Accommodation and food, Mining, Arts and recreation, Rental, hiring and real estate services, had 7% of software capex and capital stock in 2023-24. These industries make up 19.3% of industry gross value added, of which Mining is 10.4%.

The software intensive industries are all services, and it is notable that the goods producing industries of Agriculture, Construction, Manufacturing and Mining are in the bottom half of industries for the value of their capital stock. With the exception of Agriculture, which has the lowest capital stock but high productivity growth, the other three are among the productivity laggards in Australia, and have had little or negative labour productivity growth over the last few years.

The link between productivity and software capex and capital stock is, however, a weak one. Training and learning is required for new software, there are often features in a software system that are not used, software and IT investments will often be disruptive and taking advantage of new systems needs reorganisation, redesigned processes and restructured roles. Small firms find all these factors more challenging than large firms with more resources and deeper skill sets, and one part of the explanations for the weak relationship between software capex and productivity growth may be the large number of small firms.

Digitisation of Australian industry is narrow and shallow. It is narrow because two industries worth 15.4% of industry gross value have 43% of total software net capital stock, and do 34% of software capex. It is shallow because adding the next two industries gives the top four industries 51% of software capital stock, 49% of capex, and 23.4% of industry gross value added. The top eight industries account for 73% of software capital stock, 71% of software capex, and 44.7% of industry gross value. The other 12 industries that make up 45% of industry gross value (the balance is in ownership of dwellings) only account for 26% of software capex and 25% of software capital stock.

An important point is that the service industries that make up the top eight have output measurement issues because they are not goods producing, and this is another part of the explanation of the weak IT/productivity relationship. A related factor may be an increase in the number of employees working with computers due to increased use of IT, but there is no way to identify and measure any change in the quantity or quality of output due to efficiency gains.

Increasing capex on software would have a marginal effect on aggregate capex. In 2023-24 total GFCF was $649 billion, with $245 billion on Non-dwelling construction the largest component, followed by $142 billion on Dwellings, $129 billion on M&E, $41 billion on Software and $27 billion on R&D. Nevertheless, raising capex on software will be a necessary element in improving Australia’s productivity growth rate because it is an important enabler of increased efficiency and leads to reorganisation of processes and organisations. Incentives to increase software capex like accelerated depreciation or tax write-offs would be effective, and could be supported with other policies to increase training and skills development. Targeting small and medium sized firms would greatly increase the effectiveness of such policies.

*

[1] Capital stock in the current year is last year’s stock minus depreciation plus new investment. The volume measure of Net capital stock is adjusted for depreciation due to wear and tear from use and changes in prices.

[2] On 5th August the Productivity Commission released their report on Harnessing Data and Digital Technology.

Subscribe on Substack here

https://gerarddevalence.substack.com/