Long-run Changes in the Number and Size of Firms in the Australian Construction Industry

There have been five Construction Industry Surveys (CIS) by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), the most recent for 2011-12. All five surveys found the construction industry is overwhelmingly made up of small firms which contribute most of the industry's output and account for almost all of the number of enterprises. Table 1 shows the breakup between contractors in Building and Engineering and the subcontractors in Construction services (which were called trades in the earlier surveys). The 2002-03 survey used different categories of businesses (not establishments) in residential, non-residential and non-building, and trade services and is not comparable with the other surveys. In 2002-03 there were 339,982 businesses of which 269,228 were trade services and 70,753 were residential, non-residential and non-building businesses.

How the size of firms is measured in the CIS has changed twice. The three surveys in 1996-97, 1988-89, and 1984-85 divided firms into three sizes: employ less than 5, employ 5-19, and employ 20 or more. The 2011-12 survey divided firms into small 0-19, medium 20-199 and large with over 200 employees. The 2002-03 survey divided firms by income and the data cannot be compared to the other surveys however, although income was used to classify firms, the 2002-03 survey produced a similar result, finding 90% of firms were small or very small. Here the 1996-97 survey and the 2011-12 survey data is presented. The breakup of firms by size is in Table 2.

In the 1996-97 survey businesses with less than five employees accounted for 94% of all businesses and over two-thirds of all employees. Less than 1% of businesses employed 20 or more. Businesses with less than five employees accounted for slightly less than half the total income and expenses, whereas businesses with employment of 20 or more accounted for almost one-third of these. The data in Table 3 is percentages, showing the importance of the 0.62% of large firms. Their 13.6% of employees earned 32.3% of salaries and wages, generated over 28% of income and nearly 25% of gross output.

The survey in 2011-12 classified firms by the number of employees into small 0-19, medium 20-199 and large with over 200. The same data for the 2011-12 survey is in Table 4. The changes between 1996 and 2012 are revealing. The total number of firms has increased marginally from 195,000 to 210,000, but the share of small firms has increased from 94% to 98% as the number of medium and large firms fell from 12,300 to less than 5,000. There was a trend with the number of medium sized firms decreasing to less than half, while slightly increasing their share of industry employment.

In 2011-12 less than 0.1% of firms were large, employing 18.6 % of the workforce, paying 32% of wages and salaries and generating 27% of industry income and 25% of output.

These are remarkably similar to the 1996-97 CIS numbers, however, the 186 large firms in 2011-12 had almost the same share of employment, income and output that 1,200 firms had in 1996-97. This was a significant increase in industry concentration. In the 1996 survey the 1,200 firms employing 20 or more had a total of 66,000 employees and accounted for 13.6% of employment and 24.4% of industry output.

In 2012 there were 186 firms employing 200 or more with 177,000 employees, accounting for 18.6% of employment and 25.5% of IVA. These long-run changes in industry structure can not only be the result of business failures, which are common with SMEs but less so for large firms. Instead, there has been a long wave of mergers and acquisitions reducing the number of large firms and increasing industry concentration.

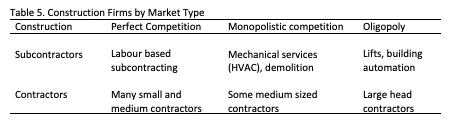

A stylized representation of construction industry firms by market type is in table 8, showing how concentrated markets can be the outcome of either firm size or specialization. Figure 5 relates market type to contract size. As a firm gets larger it takes on bigger projects and compete with fewer other firms. How construction economists sought to reconcile theoretical and conceptual models of construction firms with the messy reality of the construction industry is discussed in the next section.