And how

construction is different

Every so often a book comes along that reminds

me of the fact that building and construction is different from other industries, and highlights some interesting points about those differences. Walter Kiechel’s Lords of Strategy

was one of

those experiences.

The strategists of the title were the men who founded

the firms and created

the modern management consultant industry. These men (and with few exception the characters in the book are all men, many of them with engineering degrees) and their ideas have fundamentally changed

the world we live and work in through their effect on the corporate world, and in particular their effect on the largest global corporations that dominate the modern industrial and post-industrial economic landscape.

So this book is interesting for several reasons. The first is the story it tells about how management consulting developed from the 1960s and the manner in which it became a central player in business

development. The second is that it is really a history of ideas, or from another perspective the intellectual history of an idea. The third is the way the interaction over time between the consultants with their ideas and business facing its challenges changed both.

On the face of it the story of how management consulting developed and how it became a central

player in business development is not a promising

topic. But this turns out to be wrong, mainly because Kiechel knows so much about his subject

after a career

spent observing managers of major US corporations. He gives an inside account

of the birth and evolution

of strategy as the dominant business paradigm of the second

half of the twentieth

century.

The founder of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), Bruce Henderson, was the originator of business strategy as we know it today. His first insight was the importance of the experience curve, or the decline of unit costs as production volumes increase (also called the learning

curve effect). No other idea has had such a large impact on corporate

consciousness, despite

its weak empirical

support: “As the 1960s unfolded, fattish,

complacent American companies

found themselves confronted with competition from unexpected

quarters – foreign

manufacturers, smaller upstart enterprises in their own backyard. What was going on? What to do? The BCG had the answer to both questions in the form of the experience curve” (p. 31)

The large American industrial companies that turned to BCG were of course doomed to decline from their peak in the early 1970s. However BCG gave them the tools to fight back, mainly in the form of detailed

data on their costs, capital

structure, customers, competitors and market shares, data these firms had never had or needed before. This data was then integrated by BCG into a corporate strategy based on gaining

market share (to drive down costs by increasing production), not maximising short-term profits. Radical

stuff.

The best-known concept to come out of BCG is the growth-share matrix. This ubiquitous diagram of cash cows, dogs, stars and question marks pulled together

all the elements of strategy BCG thought essential. As a single,

conceptual device it was a thing of beauty that captured with brutal honesty a corporation’s situation and the decisions

to be made. It also made BCG a load of money because

analysing a company’s

product portfolio was a lot more lucrative than drawing experience curves.

In 1973 BCG’s best salesman left to form his own company.

Bill Bain wondered what happened for BCG clients

after the consultant’s report was handed in, with all the insights

and data it contained. Did the clients

make more profits? Did anyone know? Bain and Company

did

not take on projects

for clients, like BCG, but had an ongoing relationship, paid monthly, with only one client from an industry, or more exactly one client from a competitive set. With this approach Bain stole a march on its competitors by taking on implementation, the nuts and bolts of

managing a strategy.

Bain’s slogan (its value proposition) could have been “We don’t sell advice by the hour; we sell profits at a discount.” The keys to profits

were costs and processes, and Bain developed the ideas of best practice

and benchmarking, and measuring the results

by a company’s share price growth.

If you have wondered where the modern obsession

with measurable results originated, Bain and Company’s work in the 1970s and 80s would be the place to start looking.

The third global consulting firm is McKinsey and Company. The oldest of the three it was founded by an accountant in 1926, and in the 1950s and 60s had focused

on helping large companies shift from a functional

to the new divisional model of organisation. However in

the 1970s it was in the doldrums and falling behind its competitors. The book tells the story of how

Fred Gluck went from being a rocket scientist for Bell Labs to the founder of McKinsey’s strategy practice, and in the process

turned it into a firm of “strategy buffs”. Indeed, by the mid-1980s McKinsey had arguably become the strategy

firm, and had put the full weight of its prestige and reach behind the strategy revolution started by Bruce Henderson.

The next character introduced is Michael

Porter: “who would eventually become the most famous business-school professor of all time. To get there, though,

he would have to fight off academic elders who wanted to deny him a job, and then thoroughly disrupt both the curriculum

and the pedagogy

of the Harvard Business School.”

(p. 117)

When Porter’s book Competitive Strategy came out in 1980 it may have built on the consultants’ previous work, but it also laid out the possible choices of strategy (three) more clearly

than anything done before, and put strategy at the centre of both business management and business school teaching. The book is now past its sixtieth printing and business education has never been the same since. The story of Porter’s experience at Harvard is an engrossing

example of overcoming entrenched conservatism in academia.

One of the criticisms of Porter’s

ideas is the lack of a human element, his corporations do not appear to have people working in them. In 1982 Tom Peters and Robert Waterman’s book

In Search

of Excellence put that right, and

went to the top of the best-seller lists. Peters had left McKinsey a few months earlier and Waterman

left after the book’s success.

They emphasised the centrality of people to a company’s success, although this turned out to something

of a

short-term victory against the prevailing management view.

Excellence also turned

out to be difficult, within five years half of the 43

companies on Peters and Waterman’s list were in trouble. The wave of similar

books that followed, with their stories of success, all found the same problem.

Success is transitory, performance is impermanent, but corporations, especially large corporations, go on. More precisely, the human factors

like norms and behaviours that make up what we call corporate culture persist. This turned the focus of attention

onto the implementation of strategy, which is neither as sexy nor as stimulating as solving

problems for a new client. What it did do was build client relationships and make Porter’s value chain the closest

thing we have to a universal

concept in business

strategy.

Over the final chapters Keichel surveys a number

of the key features of the contemporary corporate landscape. These include financial engineering, leverage and buyouts, the arrival

and departure of core competencies and capabilities, and the impact of technological development and the internet.

This is all interesting stuff, although these chapters lack the focus of the earlier

part of the book, and unlike the original ideas in the strategy

revolution none of these ideas are secrets because they have been extensively promoted by their authors.

What they do is highlight

just how influential in forming the contemporary corporate landscape

the original ideas of the strategy merchants have been.

That is one of the genuinely important insights this book gives us. Many of the conventional wisdoms heard from chief executives

are recycled and retreaded

ideas from the early days of the strategy

revolution. For better or worse, these ideas have been instrumental in the development

of many modern management methods, and in doing so have directly

affected the

lives of millions.

Construction is different, strategy is difficult

This post started by observing

how the book shows up differences between the building

and construction industry and manufacturing, and later

banking and finance, industries where the strategy

consultants were most influential. The most significant difference is the limits to strategy in an industry

based on tendering

and low-price competitive bidding.

For the great majority

of projects price is the only strategy.

There are contractors that specialise in a particular type of work, Westfield in shopping malls for example, and some have become geographically diversified

through takeovers, but these are the exceptions that prove

the rule that strategy is not an

important factor for most

contractors.

The second key difference is the lack of a meaningful experience curve effect. Costs are not closely

related to volume or market share, so Bruce Henderson’s idea would not have much impact on a construction firm. Closely allied to this is the lack of opportunity and/or unwillingness of most clients to invest in developing long-term relationships with contractors and other industry suppliers.

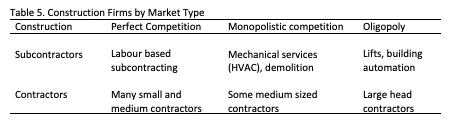

That said, construction is a more diverse

industry than most, in terms of types of projects and

characteristics of firms. It may be that the

technological or organisational conditions for a strategy revolution

in construction have not

yet been put in place, or perhaps it will require new entrants to apply new ideas about processes and production and bring innovative strategies with them into the industry.

Walter Kiechel III, The Lords

of Strategy: The secret history of the new corporate world, Boston: Harvard Business

Press, 2010.