Why Modern Methods of Construction Don't Work

Offsite manufacturing, modular and prefabricated building have been transforming construction like nuclear fusion has been transforming energy: they have both been twenty years away from working at scale for the last 60 years. These ‘modern methods of construction’ have a dismal track record. The brutal economies of scale and scope in a project-based, geographically dispersed industry subject to extreme swings in demand have always bought previous periods of their growth and development to an end.

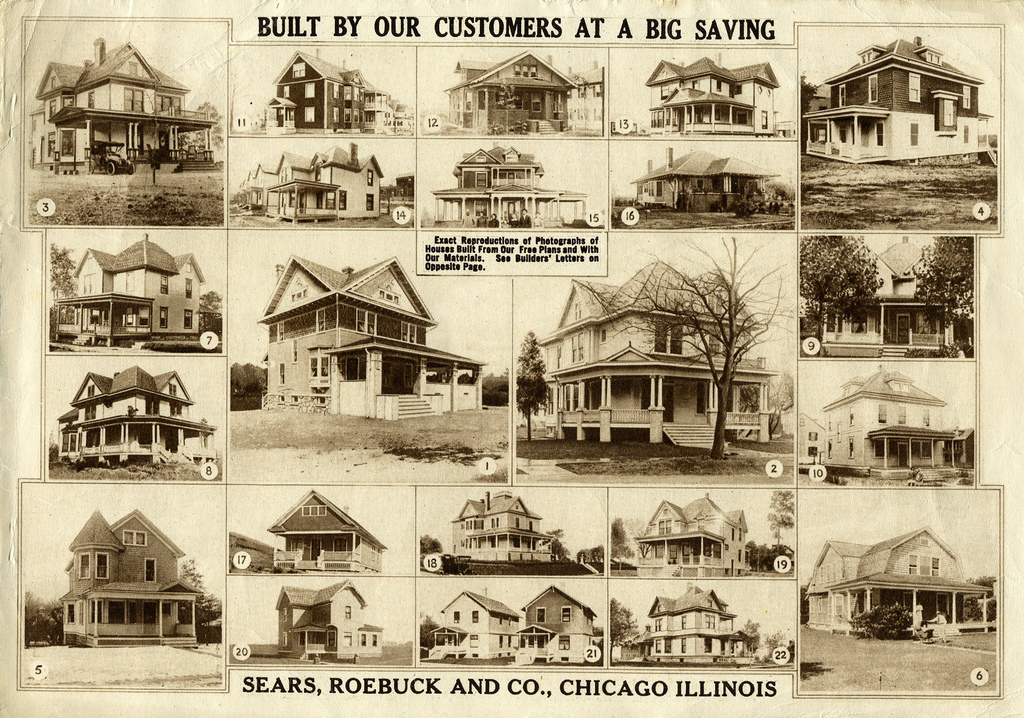

While the history of prefabrication features major projects like the Great Exhibition in 1855 and more recently the Oresund Bridge in 2000, the reality is that prefabrication has only been successful in specific niche markets such as institutional buildings, or house manufacturers like the Japanese and Scandinavian firms Sekisui and Ikea. Failures like Katerra in mid-2021 and the mail order houses sold by Sears Roebuck a hundred years ago in the US are common. In the UK 2017 Industrial Strategy Construction was one of the four Sector Deals along with AI, the car industry and life sciences, with the aim to change the way buildings are created with a manufacturing hub for offsite and modular construction. By 2021 the focus had moved on, to the energy efficiency of buildings and new design standards.

The up-front capital requirements of prefabrication make it a capital-intensive form of production, which brings high fixed costs in a cyclic industry characterised by demand volatility over the cycle. This means macroeconomic events often determine the success or failure of the underpinning business model and the success or the eventual failure of the investment. A batch of new US prefab housing firms failed during the GFC after 2007, for example, demonstrating the importance of the relationship between economic and business conditions and the viability of the business model for industrialised building.

Manufactured housing in the US also provides an insight into the institutional barriers to industrialisation in construction that exist in many countries and cities. Although the Department of Housing and Urban Development hasa national code, US cities discriminate against manufactured housing as local and county governments use a variety of land use planning devices to restrict or ban their use, and often place them in locations far from amenities such as schools, transportation, doctors and jobs. Despite these barriers, in 2021 there were 33 firms with 136 factories that produced nearly 95,000 homes.

An ambitious attempt at offsite manufacturing (OSM) and industrialized building was made by Katerra, a US firm that was reinventing construction but has now gone into receivership. The manufacture of building elements and components somewhere other than the construction site has been variously called prefabrication, pre-cast and pre-assembly construction. Types of offsite construction are panelised systems erected onsite, volumetric systems that involve partial assembly of units or pods offsite, and factory built modular components or pods. The degree of OSM and preassembly varies from basic sub-assemblies to entire modules. Katerra manufactured prefabricated cross laminated timber (CLT) structures.

Katerra

Katerra was a Californian start-up, founded in 2015. In 2017 it reached a $1 billion valuation, The company’s goal was complete vertical integration of design and construction, from concept sketches of a building to installing CLT panels and the bolting it together. On their projects the company wanted to be architect, offsite manufacturer and onsite contractor. This led to issues with the developers and contractors the company dealt with most of whom, it turned out, didn’t want the complete end-to-end service Katerra offered.

The company started by developing software to manage an extensive supply chain for fixtures and fittings from around the world, but particularly China, and then added a US factory making roof trusses, cabinets, wall panels, and other elements. In 2016 the business model changed because architects weren’t specifying Katerra’s products. Katerra would design its own buildings and specify its own products. In 2017 it built a CLT factory that increased US output by 50 percent. The factory shut in 2019. Dissatisfied with design software that didn’t meet its needs, it developed a custom suite called Apollo. This was to be a platform for project development and delivery, well beyond the document control and communication of then available software from Oracle Aconex, Trimble Connect, Procore and SAP Connect. Apollo integrated six functions:

1. Report: use an address to find site information, zoning, and crime rates etc.;

2. Insight: design with the two building platforms;

3. Direct: a library of components used in the building;

4. Compose: for coordination between the different groups working on a project;

5. Construct: for construction management (similar to Procore and Bluebeam):

6. Connect: for managing the workforce on a project, with a database of subcontractors.

One of the company’s three founders was a property developer, and his projects provided the initial pipeline of work that made the company viable. Initially, buildings were designed by outside architects, but in 2016 the company started a design division. A second founder had a tech venture capital fund, the third and CEO did a stint at Tesla. Their ambition was to leverage new technologies to transform building by linking design and production through software, designing buildings in Revit and converting the files to a different format for machines in the factory.

In 2018, after raising $865 million in venture capital led by SoftBank’s Vision Fund, Katerra acquired Michael Green Architecture, a leading advocate of CLT, and over a dozen other architects and contractors. In 2020 the business model changed again, by taking equity stakes in developments to boost demand. Katerra struggled to complete the projects. Accumulating losses and cost overruns during the Covid pandemic overwhelmed the company and in June 2021 Katerra Construction filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

In six years Katerra had grown to a 7,500 person company. That growth cost both money and focus, of the total US$2.2bn raised, SoftBank invested $2bn between 2018 and 2020. Without a clear focus, Katerra didn’t have a target customer base and got distracted by software and developing internet-of-things technology. The executive team was dominated by industry outsiders, but Katerra hired architects and engineers from traditional firms. Tension was inevitable. The fatal problem was execution, Katerra didn’t vertically integrate acquisitions into a company that did everything. It was fragmented and didn’t have a product platform or Apollo ready in time.

With Apollo, Katerra was actually behind other companies developing platforms that manage design and construction in various ways. These platforms are at the technological frontier, a fourth industrial revolution technology for OSM with automated production of components. Other firms have developed different approaches to digital manufacturing and restructuring of firm boundaries to Katerra, integrating design and construction through development of digital platforms that provide design, component specification and manufacturing, delivery and on-site assembly.

For example, in 2018 Project Frog released KitConnect, bringing together a decade of development into prefabrication and component design, and integrating BIM with DfMa and logistics. US start-ups in the wake of Katerra like Junoand Generate also don’t build factories but outsource assembly. Outfit offers homeowners a DIY renovation from its website, then orders and ships the materials and provides step-by-step instructions for completing the work (the Sears model again). Also in 2021, the IPO for PM software company Procore raised $635 at a valuation near $10bn, a record for construction tech. Rival Aconex was bought by Oracle in 2017 for $1.2bn. Platforms are in the process of becoming a basic part of construction tech. In the UK Pagabo launched a procurement platform in 2021, mainly for the public sector, using framework agreements for building work valued between £250k to £10m. Australian 2021 procurement IPO Felix had local start-ups Buildxact, SiteMate, Mastt, Portt and VenderPanel with competing platforms.

Conclusion

The idea of construction as production was based on OSM, but after decades of development has yet to become a viable business model. There have been successes in manufactured housing, but often macroeconomic factors undermined their viability. Niche markets exist in institutional building, or wherever it is the most effective or efficient piece of technology available. This manufacturing-centric view of progress in construction, endorsed by numerous government and industry reports, is the end point of the development trajectory from the first to the third industrial revolutions.

The technological base of OSM is a mix of those from the first industrial revolution, like concrete, with second and third revolution technologies like factories and lean production. Despite all efforts this has not become a system of production because OSM does not deliver a decisive advantage over onsite production for the great majority of projects. Instead, construction has a deep, diverse and specialised value chain that resists integration because it is flexible and adapted to economic variability. Policy makers may neither like nor appreciate this brute fact, but economies of scale are the economic equivalent of gravity and OSM has not delivered.

The constraints of OSM have outweighed the drivers and benefits. At this stage the market share of OSM remains small and niche, estimates are low single digits of total construction work in the UK, US and Australia. Success elsewhere is restricted to a few specific markets and project types. The problem is not the technology, which can be made to work, but the expected economies of scale are difficult to achieve because of a range of factors. Some of these factors are internal to construction, but others are external. In particular, macroeconomic events like financial crises or energy and commodity price changes can quickly undermine a business model.

Norman Foster said in an interview ‘A building is only as good as its client’. With industrialized building the client is the producer, which is not necessarily a bad thing, however this has restricted its use to niche markets. How to apply the technologies of the fourth industrial revolution so they work with the economies of scale for onsite production in construction, beyond the OSM paradigm that has been followed for years without success, is the challenge