Grattan Institute Transport Infrastructure Report

The Grattan Institute, a Melbourne based think tank for public policy, released an important report into procurement of Australian transport infrastructure projects. Their Megabucks for Megaprojects report has four chapters and makes 12 recommendations. The chapters contain a lot of carefully compiled and useful information, while the recommendations are all worthy and, despite their careful phrasing, make a strong case for greater client involvement in the design, documentation and management of large public sector projects.

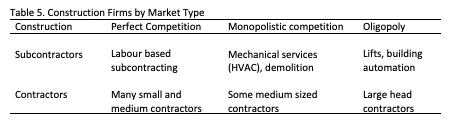

Chapter 3 of the report is ‘Competition is fundamental’, addressing the issue of the dominance of tier one contractors. The chapter collects data on projects and contractors that is not readily available, with the sources and methodology detailed in the appendices. Their key point is the increase in size of projects since 2014, as shown in Figure 3.3 below.

For the last few years the quarterly value of work done on these large transport projects has been over $5 billion. In 2020 Australian governments spent a record $120 billion on road and rail transport projects.

The argument is that it is increasingly difficult for mid-tier contractors to win work on these very large projects, of the 11 projects above $3 billion 8 were ‘contracts involving multiple tier one firms’. These firms are ‘few and well-known’ in Australia and their Figure 3.10 shows how few, and how they consolidated their position through M&A over the last couple of decades.

The two sources of potential competition for the three tier one contractors are domestic rivals that might scale up sufficiently or new international entrants to the Australian market. In chapter 4 the report argues strongly for breaking up large contracts to allow greater participation from domestic firms, Recommendation 10 is: State governments should develop and use a systematic approach to determining an optimal bundling of work packages for large projects, including when to disaggregate bundles that include both complex and straightforward activities. While not a new idea it is still important because public clients do not generally do this, and often do not have the resources required to manage multiple contracts.

That leaves international entrants, which the report argues have been playing an important role since 2005: ‘International entrants add to local competition, and it’s very helpful to governments if there are a variety of market players willing and able to take on work. In particular, when tier one firms form a joint venture to bid on a large contract, the only source of genuine competition may be from international firms’. Their Figure 3.5 shows the distribution of contracts between new international entrants and firms that were already here in 2006. Of those firms, Bouygues won 4 contracts, Lang O’Rourke and Acciona 5 each.

There are barriers to entry when bidding for these contracts, on top of the high bid costs. These are the lack of transparency in the weighting given to selection criteria and the emphasis on local experience. The report’s Recommendation 8: In selecting a successful bidder, governments should not weight local experience any more heavily than is justified to provide infrastructure at the lowest long-term cost. Governments should publish weightings of the criteria used to select the winning bid for a contract. The Grattan Institute is strongly opposed to ‘market-led proposals’ from contractors, and strongly in favour of open tendering. The state with the highest transparency rating is NSW, also the state with the most contracts with new international entrants.

The report collects data on 51 projects over $1 billion in Australia since 2006. Their dataset of transport infrastructure projects includes 177 contracts worth more than $180 billion (in December 2020 dollars). That data makes this an important contribution to the debate about construction industry policy in Australia, to the limited extent that there is such a debate. A couple of decades ago this data would have been published by the Commonwealth, by the Department of Industry or similar organization, and incorporated into the procurement guides being developed by the Australian Procurement and Construction Council and related State agencies. The report concludes “these guidelines leave a great deal of room for subjectivity in the choice of contract type. Although some of the state guidelines and decision-support documents are quite detailed, none go so far as to prescribe a rigorous and systematic methodology for procurement strategy selection.”

This raises the awkward question of who the report is addressing. The fundamental problem is the politicization of the project selection process not the cost of delivery, Australian construction is not expensive by international standards. The recommendations address the problem obliquely by highlighting improvements in procedures and processes, all of which have merit, but not considering alternatives such as the role an independent authority could play or national coordination of procurement and other regulatory systems. In this it was something of a missed opportunity

State and Federal budgets have billions in unallocated funds for projects at all levels (community sports grants, local and regional infrastructure) and for major projects the Commonwealth has Snowy Hydro, the NAIF, the Murray-Darling Basin Plan etc etc. These projects, large and small, shovel money out the door with little or no accountability and there is no evidence that politicians are interested in change at this time.