Off-site manufacturing, modular and prefabricated building have been

transforming construction like nuclear fusion has been transforming energy:

they have both been twenty years away from working at scale for the last 60

years. The brutal economies of scale and scope in a project-based,

geographically dispersed industry subject to extreme demand swings have bought previous periods of success to an end, one reason the history of prefabrication features major

projects like the Great Exhibition in 1855 and more recently the Oresund Bridge

and Crossrail’s tunnels and stations. At an industry level, prefabrication has

been successful in specific niche markets, like institutional building in the

UK, or house manufacturers like the Japanese and Scandinavian firms Sekisui and

Ikea. The other problem at an industry level is the lack of standardisation,

although some countries such as the Netherlands try to address this through

their building codes.

Along the supply chain, however, many firms have integrated the various

technologies needed to produce building components and elements with the

barrier to entry, particularly for SMEs, the level of investment required. The

up-front capital requirements of prefabrication make it a capital-intensive

form of production, which brings high fixed costs in a cyclic industry

characterised by demand volatility over the cycle. This means the success or

failure of the underpinning business model can determine the success or

(typically) the eventual failure of the investment. A batch of new US prefab

housing firms went down after the GFC in 2007, for example,

demonstrating the importance of the relationship between the business model and

the viability of prefabricated building.

Another interesting characteristic of prefabricated building has been the

entry by large firms, sometimes from outside the industry, who have had the

capital to invest and an appetite for risk,

given that history. The recent news that Amazon has invested in a Californian prefabricated

housing manufacturer is therefore, possibly, important. Amazon is investing

heavily in smart home technology. This post also looks at two other firms that

are recent entrants into prefabricated and manufactured housing, UK insurance

company L&G, and vertically integrated US builder Katerra. Of particular

interest is the way these two companies are building volume, by developing a

pipeline of projects for their factories to supply. It concludes with a look at

the business model used for the mail order houses sold by Sears Roebuck a

hundred years ago in the US. By coincidence, this week Sears Roebuck missed a

debt payment and filed for bankruptcy, a reminder that no business model lasts

forever, no matter how successful.

Amazon

All the

large tech firms have venture capital subsidiaries that invest in early stage

start-ups. For Amazon it is the Alexa Fund, which provides funding for voice

technology innovation and ways to improve the way people use the technology. In

September, US start-up Plant Prefab had a $6.7 million Series A funding round

which included Obvious Ventures and the Alexa Fund. While this is Amazon’s

first investment in prefab construction, it has been selling tiny modular

houses made by MODS since last year.

Plant Prefab manufactures custom single and

multi-family homes in Rialto, California, using a patented building system. According to founder and CEO Steve Glenn, “Most existing

prefabrication companies in the US focus on standard, low quality,

non-sustainable mobile and modular homes -- for suburban communities. Plant

Prefab is unique in that we’re focused on custom, high quality, very

sustainable homes and we have a special facility and a patented building system

optimized for this. We build based on client’s architects or clients can select

from a growing number of homes we offer from world-class architects, all of

which can be customized for specific lots and client needs. By building in an

all-weather facility with lower cost and staff labour, we offer clients a more

reliable, time and cost-effective alternative to local, urban general

contractors.”

Amazon’s

investment in Plant Prefab comes with a new line of smart home

devices, suggesting the company sees a potential new market

driven by smart home technology. Amazon already has a deal with Lennar, the

largest homebuilder in the US, to pre-install

Alexa in all their new homes. There is an obvious business model here,

but also many possibilities. Amazon typically offers a combination of fee for service

and subscription services, which could be adapted for mortgage or rental

markets for example. As connectedness deepens and extends, Amazon might

potentially become a major player in the future residential building industry,

in some form.

Legal and General

Legal and General is a 180 year old British insurance company, today one

of the largest investment management firms in the world. In 2016

they announced plans to manufacture homes, however the opening of L&G’s

offsite housebuilding factory near Leeds has seen, and is seeing, many delays.

Although the first units were delivered in mid-2017, regular production is only

now being achieved and the factory is expanding. L&G is targeting

affordable housing, and set up a subsidiary called Legal and

General Modular Homes:

Our Vision is ambitious and is underpinned by our mission statement; “We

deliver desirable homes through the industrialisation of volume housing

supply”. Legal & General has a long heritage in providing housing in the UK

and sees modular construction as a natural evolution and extension of its

position in this market. Modular construction is set to revolutionise the house

building sector bringing new materials along with methods and processes used in

other industries, such as automotive and aerospace, to raise productivity and

help to address the UK’s chronic shortfall of new homes. Our investment in Europe's

largest modular homes factory demonstrates our ambition to inject capital into

the Housing sector alongside the creation of our Build to Rent, Later Living

and Housebuilding businesses. Located in Sherburn in Elmet, near Leeds, our

550,000 sq ft factory produces a range of typologies with the capacity to

produce up to 3,000 homes per year, employing several hundred local people.

The business model is this: “Legal & General Capital is building a more natural and sustainable model – one in which institutional investors are the long-term holders of the assets working alongside the best-in-class affordable housing operators who will provide the highest-quality housing management."

The business model is this: “Legal & General Capital is building a more natural and sustainable model – one in which institutional investors are the long-term holders of the assets working alongside the best-in-class affordable housing operators who will provide the highest-quality housing management."

L&G has

been investing heavily in the UK housing market over the last few years, and

aims to become the leading private affordable housing provider in the country,

with Legal & General Affordable Homes delivering 3,000 homes a year by

2022. They have a current pipeline of around 2,000 build-to-rent homes. And in

April 2018 L&G's investment arm bought the half share it didn’t own in

Cala, for £315mn, a property developer with a pipeline of 3,000 homes. L&G

also run retirement villages, they have 7 with 1,100 homes. By one estimate, L&G’s

total investment in build-to-rent currently stands at £1.5bn, with the aim to

have 6,000 homes in planning, development or operation by the end of 2019.

Katerra

Katerra is another Californian start-up, founded in 2015. In 2017 it

raised $130 million in a Series C funding round, reaching a $1 billion

valuation, The company’s goal is complete vertical integration of design and

construction, from concept sketches of a building to installing the bolts that

hold it together. On its projects the company is typically the architect, off-site

manufacturer and on-site contractor, and usually contracts directly with

owners.

The company started by developing the software to manage an extensive

supply chain for fixtures and fittings from around the world, but particularly China,

and then added a factory in Phoenix making roof trusses, cabinets, wall panels,

and other elements. In September2017 it announced plans to build a factory that will make

panels of cross-laminated timber, a high-tech structural wood, and later said

it planned to open up to seven more plants and warehouses around the US as the

business model gets rolled out.

One of the company’s three founders is a multi-family developer, and his

projects provided the initial pipeline of work that made the company viable.

Initially, buildings were designed by outside architects, but in 2016 the

company started a design division. In 2018, five months after raising another $865

million in venture capital from funders led by SoftBank’s Vision

Fund, Katerra acquired Michael Green Architecture and architects Lord Aeck

Sargent. The latter brings a healthy order book across a wider range of

buildings, the former is a leading advocate of CLT and high-rise buildings.

Katerra is essentially a technology play. A second founder has a tech

venture capital fund, the third and CEO did a stint at Tesla. Their ambition is

to leverage new technologies to transform building by linking design and

production through software. It designs buildings in Revit and then converts

the files to a different format for machines in the factory. Also, SAP HANA, a

real-time data processing application, and the Internet of Things are used to

achieve “deep integration and newfound efficiencies.” A nice time lapse of one

of their buildings is here:

Mail Order Houses

A bit over a century before Ikea sold their first Boklok house, one

fifth of Americans were subscribers to the Sears and Roebuck Mail Order

Catalogue. Anyone anywhere in the country could order a copy for free, look

through it, order something, and have it delivered to their door. At its peak

the Sears catalogue offered over 100,000 items on 1,400 pages, and in 1908 they

began offering houses.

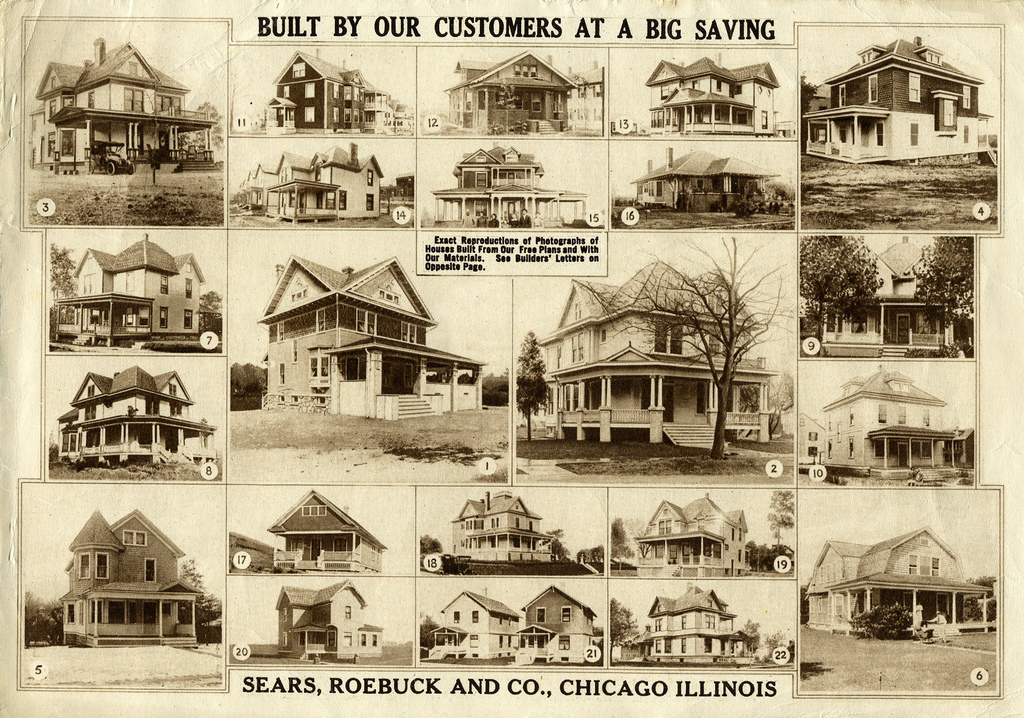

While not the first company to sell kit homes by mail order, Sears came to

dominate the mail-order market. Between 1908 and 1940 it delivered 75,000 homes.

The Sears Modern Homes Program offered

complete houses, what would now be called ‘kit homes’. Customers selected from

dozens of different models, then they could order blueprints, send in a check,

and a few weeks later a train car would arrive with the door secured by a small

red wax seal. The new owner would open up the boxcar to find over 10,000 pieces

of framing lumber, 20,000 cedar shakes, and everything else needed to build the

home. The lumber came precut with an instruction booklet, and Sears promised

that, without a carpenter, a person could finish their mail order home in less

than 90 days.

Then, in

1911, Sears began offering mortgages to their customers. The Sears home

mortgage program became one of the keys to success (all those homes, and their

new, mostly young homeowners, needed furnishing and decorating and so on). In

lowering the barrier to entry, it allowed Sears to sell more kit homes faster

than any of its competitors. But when the Great Depression came things got

ugly, over the 1930s the company ended up foreclosing on tens of thousands of

its customers. It was a public relations disaster.

After years

of declining sales, Sears finally closed its Modern Homes department in 1940. A

few kit home manufacturers that hadn’t sold mortgages survived, but the

Sears boom was over. The next housing boom was the rise of the suburbs

and the prefab home. As demand surged in the postwar years, US companies such

as Lustron and the National Homes Corporation factory built homes by the thousands.