Heathrow

Airport’s Terminal 5 is one of the most extensively documented megaprojects. Built

by British Airport Authority (BAA) and completed in 2007 there is a book, a

volume of ICE Proceedings, numerous academic journal and conference papers, and

many more newspaper and magazine articles. Apart from its size, cost, and

enormous numbers, the distinguishing feature of T5 is that it came in on time

and on budget, one of the few megaprojects to do so. How that was achieved is,

I think, an interesting story.

The foundation

was the T5 Agreement, a sophisticated incentive contract between BAA and its suppliers,

a large and diverse group of traditionally competitive engineers, architects and

design consultants, specialised subcontractors, general contractors,

fabricators and manufacturers. The

supplier network had 80 first-tier, 500 second-tier, 5,000 third and 15,000

fourth-tier suppliers. Over 50,000 people worked on the site at some point during construction. This was an unusually collaborative approach, with BAA taking

responsibility for project management using the complex incentive contract to minimize

risk.

The purpose of a procurement

strategy is finding the most appropriate contract and payment mechanism. An

effective procurement strategy enables an ability to manage projects while

dealing with changes in schedule, scale and scope during design and delivery. This is the

trinity of time, cost and quality in building and construction. The bigger the

project, the harder it gets. For BAA the investment in T5 was around the same

as the then value of the company, and the government imposed significant

penalties on late completion and underperformance.

Two commonly

used categories of explanation for cost overruns and benefit shortfalls in

major projects are technical and psychological, Technical explanations revolve

around imperfect forecasting techniques, such as inadequate data, honest

mistakes and lack of experience of forecasters. Psychological explanations

focus on decisions based on unrealistic optimism, rather than a rational

scaling of gains, losses and probabilities.

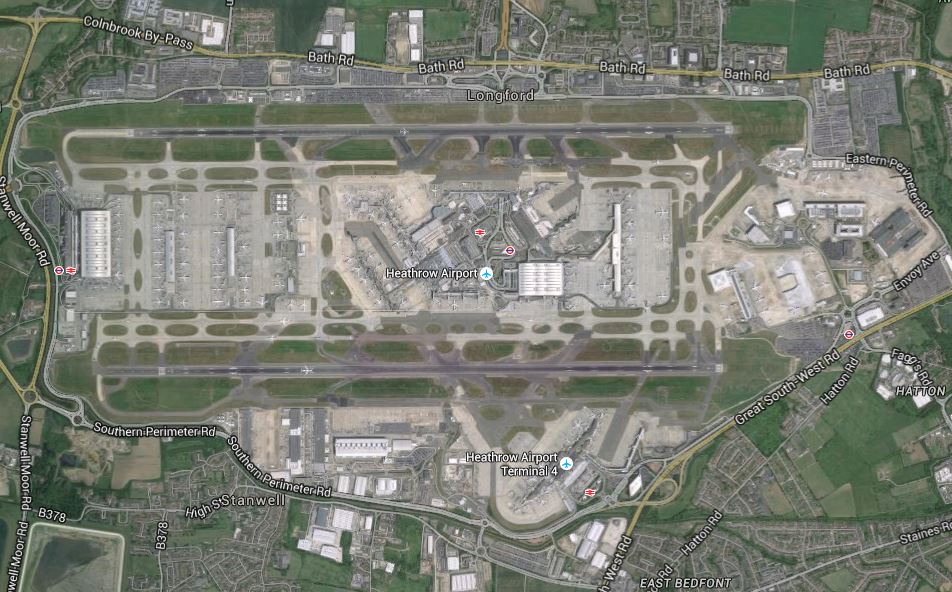

T5 is on the left side if the picture. It included the main terminal building and two satellites,

62 aircraft stands, an 87m air traffic control tower, car parking for 5000

vehicles and a hotel, road and underground rail and services infrastructure. There

were 1,500 work packages in 147 subprojects, clustered into 18 projects led by

4 project heads for civil engineering, rail and tunnels, buildings, and systems.Two

rivers were diverted around a site of 260 hectares, and the T5 building itself is

40m high, 400m long and 160m wide.

Before work

started on T5, BAA studied a group of similar projects and the problems they

had encountered, known as a reference class. It is a process based on pooling relevant

past projects to identify risks and get a probability range for outcomes. For

example, the reference class based forecast for fatalities on a project the

size of T5 was six, with the safety program the actual outcome was two.

Using this reference

class to forecast time and cost performance by estimating probability ranges

for T5, BAA designed a procurement strategy. BAA was a very experienced client

and they dealt with these issues in a systematic way. Under Sir John Egan they had

started a program called CIPPS, which produced the first iteration of the T5

Handbook in 1996. This was revised as test projects completed, and by 2002 a

budget of £4.3bn and schedule of 5 years was in place.

The procurement

strategy for T5 centered on managing innovation, risk and uncertainty. BAA’s

management team recognized the size, scale and complexity of the project

required a new approach if the project was to succeed. The contractual

framework was envisioned as a mechanism to permit innovation and problem

solving, to address the inherent risks in the project.

BAA used in

house project management teams to create relationship-based contractual

arrangements with consultants and suppliers. Traditional boundaries and

relationships were broken down and replaced by colocation, so people from

different firms worked in integrated teams in BAA offices under BAA management.

The focus was on solving problems before they caused delays.

An example of a T5 innovation in design management was the Last

Responsible Moment technique, borrowed from the lean production philosophy

developed by Ouichi Ono for Toyota. LRM identifies the latest date that a

design decision on a project must be finalised. The method implies design

flexibility, which is logically an approach used when there is unforeseeable

risk and uncertainty, but once the decision is made the team takes

responsibility and the task is to make it work.

The contractual

agreement developed was a form of cost-plus incentive contract. However, unlike

other forms of cost-incentive contracts where the risks are shared between the

client and contractors, under the T5 Agreement BAA assumed full responsibility for

the risk. The client explicitly bearing project risk was a key innovation that

differentiates T5 from many other megaprojects.

Because BAA

held all the risk, suppliers could not price risk in their estimates, which

meant that they had to maximize their profit through managing performance. BAA

used an incentive based approach with target costs to encourage performance and

proactive problem solving from suppliers. Although there is a risk with

over-runs, the risk is hedged on the basis contractors will strive to achieve

cost under-runs in order to increase their profit.

The incentive

was paid as an agreed lump sum based on the estimate for a particular

sub-project (the target cost). If suppliers delivered under budget than that

extra amount of profit would be split three ways between the suppliers and BAA,

with a third held as contingency until the project completed. Conversely, if

the suppliers took longer than expected or more funds were needed to finish a

project, it would affect their profit margin.

Through the T5

agreement, and the planning that went into developing it, BAA was able to set

performance standards and cost targets. The integrated teams focused on solving

problems and, with the alignment of goals and the gainshare/painshare financial

incentives in the Agreement, suppliers were able to increase their profits.

The T5

Agreement’s financial incentives rewarded teams for beating deadlines for

deliveries, and was project team based, as opposed to supplier based, to

encourage suppliers to support each other. BAA paid for costs plus materials,

plus an agreed profit percentage which varied from 5 to 15% depending on the

particular trade. With full cost transparency, BAA could verify costs had been

properly incurred. BAA was able to audit any of their suppliers’ books at any

time including payroll, ledgers and cash flow systems.

*

Megaprojects

have a terrible track record of cost overruns, which is why the reporting on T5

is so positive. It was an exceptional project in every respect and, like many

megaprojects, became a demonstration project for introducing new ideas into the

industry. Once construction started, the delivery of T5 on time and on budget,

with a remarkable safety record, was due to the three inter-related factors of risk

management, integrated teams, and the alliance contract. BAA held all the risk and

the incentive contract meant suppliers could gain through performance. Instead

of risks and blame being transferred among suppliers, followed by arbitration

and litigation, BAA managed and exposed risks, and the suppliers and

contractors were motivated to find solutions and opportunities.

The T5 Agreement highlights the

fact that procurement as a strategy is primarily about finding an appropriate

mix of governance, relationships, resources and innovation. There were three

iterations of the Agreement, as it developed in stages through trial and error.

The values written into the T5 Agreement stated

‘teamwork, commitment and trust’ as the principles that BAA as the client and

project manager wanted from suppliers and contractors. This was achieved through a partnering or alliance approach, driven down through the supply

chain by the 80 firms in Tier 1 to Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers. The procurement

strategy and T5 Agreement helped popularize the framework agreements in use

today, where major clients find long-term industry partners for building and

construction work.

The success of

T5 was also a successful translation of the Toyota lean management paradigm, bringing

co-location, integrated teams, LRM design management and other lean techniques,

and cooperative relationships into a megaproject environment. BAA invested so

heavily in preparing for T5 because of the risk the project presented, effectively

they were betting the company on the outcome. They built two logistics centres on-site,

and a rebar workshop, to minimize delays in the supply chain.

Not many

projects have the unique combination of scale, circumstances and complexity found

in T5. Nor associated stories like decades of planning inquiries or the failure

of the baggage handling system on opening day. As a highly visible and

controversial project, and at the time the largest construction project in

Europe, it was also unusually well documented.

This is the third in a series of procurement case studies. The previous ones were on the building of the British parliament house at Westminister in 1837 and the Scottish parliament's Holyrood Building in 1997.

Some T5

Publications

Brady, T. and

Davies, A. 2010. From hero to hubris – Reconsidering the project management of

Heathrow’s Terminal 5, International Journal

of project Management, 28; 151-157.

Caldwell, N D,

Roehrich, J K, Davies, A C, 2009. Procuring

complex performance in construction: London Heathrow Terminal 5 and a Private

Finance Initiative Hospital, Journal

of Purchasing & Supply Management, Vol. 15.

Davies, A., Gann, D., Douglas, T. 2009. Innovation in Megaprojects: Systems

Integration at Heathrow Terminal 5, California Management Review, Vol. 51.

Deakin, S. and

Koukiadaki, A. 2009. Governance processes, labour-management partnership and

employee voice in the construction of Heathrow T5, Industrial Law Journal, 38 (4): 365-389.

Gil, N. 2009. Developing

Cooperative project client-supplier relationships: How much to expect from

relational contracts, California

Management Review, Winter. 144-169.

Potts, K. 2009.

From Heathrow Express to Heathrow Terminal 5: BAA’s development of Supply Chain

Management, in Pryke, S. (Ed.) Construction Supply Chain Management,

Oxford: Blackwell.

Potts, K. 2006.

Project management and the changing

nature of the quantity surveying profession – Heathrow Terminal 5 case study,

COBRA Conference.

Winch, G. 2006.

Towards a theory of construction as production by projects, Building Research and Information,

34(2), 164-74.

Heathrow Terminal 5: delivery strategy. Proceedings

of the ICE - Civil EngineeringAll the papers in this Issue were on T5.