The extent of prefabrication used in Australian construction is unknown and unknowable

The Australian construction industry is supplied by an extensive manufacturing base that includes a wide and varied range of industries, producing machinery and equipment as well as materials like bricks, glass, concrete, steel and wood. In 2021-22 there were 133,216 people employed in construction related manufacturing in Australia.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics also includes prefabricated buildings in manufacturing, however, the data is limited to the relatively small number of firms that classify themselves as prefab manufacturers, and misses offsite work by firms that may be classified as building or trade contractors, architectural or engineering practices, or work done inhouse in other industries like tourism and aged care.

Therefore, the actual extent and depth of prefabrication used in Australian construction is unknown, and with the data available is largely unknowable. With offsite manufacturing in general, and prefabrication in particular, seen as important to addressing the industry challenges of sustainability, productivity and skills, the lack of data on how many and what type of prefabricated buildings and components are produced each year in Australia is a significant gap in knowledge and understanding of the industry.

This research starts with the ABS Manufacturing industry data. It then looks at their estimates of the number of dwellings on manufactured home estates and the effects of misclassification on those estimates. The next question addressed is the number and type of firms producing prefabricated buildings.

Construction Related Manufacturing

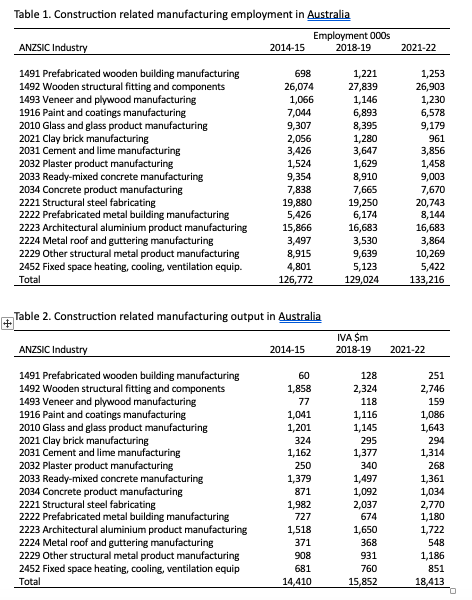

Australian Manufacturing is divided by the ABS into 19 subdivisions, with the subdivisions made up of groups of firms classified by similarities in their products or processes into classes. The ABS gives an industry class an ANZSIC four digit number, and that level of detail allows an estimate of the employment and output of construction related manufacturing to be made. The data comes from the ABS annual publication Australian Industry.

The largest of the relevant classes are for widely used materials like wood, concrete, steel and glass. Other classes include manufactured products like plaster and ventilation systems. Table 1 shows the industry classes identified as directly contributing to new construction, with the number of people employed in June, and in Table 2 their output as Industry value added (IVA) in current dollars. Figure 1 shows the totals.

Figure 1. Total employment and output

In 2021-22 construction related manufacturing was 16% of total manufacturing IVA and employment, having increased from 15% in 2014-15.

Firms self-select the ANZSIC industry code used to classify them into an industry class. Some building companies like Sekisui Australia, Hickory and Hutchinson have offsite facilities but are not manufacturers. A smaller builder that does some modular or offsite construction might be classed as a building contractor or a construction trade such as Carpentry services. Prefabricated buildings produced inhouse by an organisation in an industry like transport, tourism or retirement villages will not be included in manufacturing.

Therefore, there is some give and take as regards to what is included in and excluded from these industries, an outcome of the ANZSIC classification system. Some building products are not included, like floorboards, carpets and insulation, because they belong to larger product groups and can’t be separated in the data. On the other hand, industries included here like Glass products and Paint and coatings supply a range of other industries besides construction.

The four largest manufacturing industries supplying construction add up to nearly 75,000 people employed producing over $8 billion in added value in 2021-22, in Table 3.

Prefabricated Buildings and Concrete

There are two industries producing prefabricated buildings, of wood and metal respectively. These have grown significantly since 2014, although the big jump in IVA in 2022 may be revised in next year’s release. Nearly 10,000 people produce wood and steel prefabricated buildings. The ABS does not have data on what types of buildings are produced (i.e. residential, commercial, institutional etc.). Wooden building prefab is a very small industry, in 2021-22 total income was only $688 million and IVA was $251mn, compared to prefab steel building with income of $3.5 billion and an IVA over $1.1bn.

Concrete product manufacturing employed 7,670 people, a substantial industry that produces pots and bricks, but also prefabricated elements and buildings. The precast concrete industry is highly concentrated, with six major firms (ADBRI, Brickworks, CSR, CTC Precast, James Hardie, Holcim) and a large number of small and medium size firms around the country.

The combined total of offsite construction in 2021-22 was over 17,000 people employed and an IVA of $2.4 billion.

The share of wood and steel prefabricated buildings in total construction related manufacturing (in Figure 2) increased by nearly half between 2014-15 and 2021-22. This may be the strongest signal in this data of the uptake of modern methods of construction and increasing use of offsite construction.

Figure 2. Wood and steel building’s share of total construction related manufacturing

How Many Manufactured Homes?

The 2021 ABS Housing Census dwelling location data includes manufactured home estates and long term residents in caravan parks, and there were over 10,000 of these manufactured houses in Australia, and another 2,000 townhouses and apartments (Table 5). Unfortunately, the 2016 Census housing data did not include this category. The ABS had a separate category for Retirement villages in the 2021 Census, with over 200,000 dwellings included. An unknown proportion of those retirement villages are manufactured housing.

The ABS website explains their methods:

Dwelling location data was recorded by ABS Address Canvassing Officers in the lead up to the 2016 Census as a once-off part of establishing the Address Register as a mail-out frame for designated areas. Dwelling location was also verified or collected by ABS Field Officers during the 2016 and 2021 Census collection periods.

In rare cases, an establishment may fall into more than one category of dwelling location, such as a retirement village that contains manufactured homes, or a residential park that is made up of a mixture of caravans and manufactured homes. However, a dwelling can only be allocated to a single category and in these cases a determination was made during Census processing of the most appropriate category for the dwellings in question.

And therein lies the problem, manufactured homes that are not on an estate but within a retirement village. Research on ABS data on retirement villages and manufactured housing estates (MHEs) by Lois Towart found that compared to the 2016 Census “the 2021 Census is significantly more accurate in identifying and recording retirement villages. The issue is the numbers of caravan parks and MHEs that are recorded as retirement villages. This overstates both the size of the sector and the population.”

In her study of 112 retirement villages and 101 caravan parks and MHEs in the Central Coast, Newcastle and Hunter regions in NSW, individual properties were reconciled with small area (SA1) ABS Census data for the 2021 Census. “These are retiree destinations with large numbers of retirement villages and MHEs operated as retirement living’ and “examination of classification by the ABS demonstrates that for the 2021 Census when the dwelling location for caravan parks, MHEs and retirement villages is combined, then the total population is relatively accurate. The inaccuracy is the recording of caravan parks and MHEs as retirement villages.”

How large is this problem? The Census data in Towart’s research has the total number of people living in retirement villages in 2011, 2016 and 2021 as 154,579, then 205,709, and in 2021 249,262. That increase of almost 100,000 people implies at least another 50,000 dwellings, and probably more than 60,000 given the age of this population. An unknown number of those new dwellings were prefabricated.

Some retirement village operators offer sites for relocatable homes, but these will not be classified as MHEs. The construction methods some others use will be based on prefabricated pods and modules, probably sourced locally from a small company. Much of this offsite production might be done by firms not classified as manufacturing buildings.

How Many Producers of Prefabricated Buildings Are There?

The membership directory of prefabAus lists 9 companies as ‘end-to-end modular’ builders, and there are a dozen other member companies that produce prefabricated buildings or modules. Adding results from other web searches gives a list of 39 companies:

Anchor Homes

Archiblox

Arkit

Ausco Modular Construction

Black Diamond Modular Buildings

Carbonlite

Cubehaus

Ecoshelta

Ecoliv buildings

Ehabitat

Fairweather Homes

Fleetwood Australia

Harwyn

Hickory Group

Hutchinson Builders

Hunter Valley Modular Homes

Habitech Systems

Intermode

K.L. Modular Systems

Landmark Products

Maap House

Marathon Modular

Mode Homes

Modscape

Parkwood

Prebuilt Commercial

Pretect

PT Blink

Shawood by Sekisui House

Spanbilt Pty Limited

Strine Environments

Strongbuild Manufacturing

Sumitomo Forestry Australia

Swan Hill Engineering

Uniplan Group

Valley Workshop

Volo Modular

XLam

Zen Architects

In this (undoubtedly) incomplete list there are substantial companies like Ausco, Modscape and Prebuilt, but many are small firms. Several are engineering and architectural practices that would not be classified as manufacturers. Included are large building contractors like Hickory and Hutchinson, developers like Sekisui and Parkwood, and corporates like Strongbuild and Sumitomo. XLam manufactures cross laminated timber, PT Blink has a design for manufacture and assembly (DfMA) platform. There are also firms that specialise in prefab school buildings, like Marathon, Pretect and Harwyn.

Overall it looks like a fragmented market with a few major firms and a large number of small producers, specialised by type of material and type of building produced. Because of transport costs and marketing reach, many producers would be expected to be local and focus on a region.

The diversity of firms in this list highlights the difficulty the ABS would face in measuring the prefabricated building industry. As well as manufacturing, other ANZSIC industries they come from are construction, professional services and business services. With the ABS moving away from surveys to digital data, this sort of detailed data spread across a number of industries is hard to collect. Then there is the question of defining what is prefab and modular construction, which would be needed to organise any data collected and estimate how much is being produced.

Deloitte 2023 Industry Survey

Another piece of information comes from the Deloitte Access Economics 2023 State of Digital Adoption in Construction Report, which found 34% of the 229 firms in their survey used prefab and modular construction. The survey sample was from Australia (132), Singapore (38 firms) and Japan (59 firms), and the firms were from Building and construction (144), Architecture (86), Engineering (79) and Other (65).

The survey ranked 16 digital technologies with BIM, construction management cloud software and drones used by around 40% of firm the leaders, followed by prefab and modular where, of the 229 firms, 34% are using it already and 28% are planning to in the future. The remaining 38% are not intending to use it.

That means 76 of the 229 firms use prefab, and its possible that many of them are in the Building and construction category, which would mean up to half of the 144 firms in that category are using prefab and modular. An unknown proportion of those firms are Japanese and Singaporean, where the use of prefab and modular has been supported by government policy and is more extensive than in Australia.

The report included a few more data points:

· ‘Larger businesses in the survey used significantly more technologies on average, with businesses that have more than 500 employees using an average of seven different technologies, compared with four technologies for those with fewer than 500 employees.’

· Businesses used five of the 16 technologies on average, and about 10% were using more than ten different technologies.

· Newer businesses are investing in new technologies, with ‘businesses less than 10 years old investing 80% more than those in operation for 20 years or more.’

The survey does not allow much beyond reinforcing the generalisation that large companies, particularly building contractors, are more likely to be using prefab and modular construction.

Conclusion

Construction related manufacturing is a significant part of Australian manufacturing, and its share of total manufacturing employment and IVA has increased from 15% in 2014-15 to 16% in 2021-22. There are 17 ANZSIC industry classes included in construction related manufacturing, using data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics annual publication Australian Industry.

The two industry classes for prefabricated buildings are relatively small, but have had rapid recent growth. The share of the combined wood and metal prefabricated building classes in total construction related manufacturing increased by nearly half between 2014-15 and 2021-22. However, wooden building prefab is a very small industry, employing 1,253 people in 2021-21, compared to prefab metal building with 8,144 people employed. The ABS does not have data on what types of buildings are produced (i.e. residential, commercial, mining, institutional etc.).

The ABS 2021 Housing Census found 10,000 manufactured houses in Australia, and another 2,000 townhouses and apartments . This does not include the 200,000 dwellings ABS has in a separate category for Retirement villages. An unknown proportion of those retirement villages are manufactured housing.

The ABS data also does not include offsite work done by firms classified as building or trade contractors, architectural or engineering practices, or work done inhouse in industries like transport, tourism and aged care. The problem the ABS would have measuring the prefabricated building industry is that the ANZSIC industries firms involved come from include manufacturing, construction, professional services and business services, and this sort of detailed data spread across different industries is hard to collect.

A list of 39 firms producing prefab and modular buildings was compiled from prefabAUS members and web pages. This appears to be a market with few major firms and a large number of small local producers, specialised by type of material and type of building produced. The industries they come from include engineering and architectural practices, building contractors, and corporates, and any modules or buildings these firms produce will not be found in the ABS manufacturing statistics. This is not a criticism of the ABS, it is an outcome of the classification system used internationally for industry data.

The extent and scale of prefabrication used in Australian construction is unknown, and currently is unknowable. Based on available evidence it is mainly used in specific sectors like the mining industry, education, low cost housing, aged care and retirement villages. There is no evidence that it is cost competitive with conventional construction methods for the great majority of projects. This may be because prefab is a developing industry, or because economies of scale are not as great as expected.

With offsite manufacturing in general, and prefabrication in particular, being seen as important to addressing the industry challenges of sustainability, productivity and skills, this lack of data is regrettable, and the lack of data on how many and what type of prefabricated buildings and components are produced each year in Australia is a problem if an objective of industry policy is to increase the use of prefab and modular construction.