New estimates for output per hour worked 2011-12 to 2022-23

In September the Australian Bureau of Statistics released their estimates of hours worked by industry for state and territories. Combining those estimates with state and territory chain volume measures of industry Gross Value Added (GVA is output value adjusted for inflation) for the Construction industry gives GVA per hour worked, which is a measure of construction labour productivity. The ABS produces industry productivity estimates at the national level, but not for states and territories, so the construction productivity estimates here for the states and territories have not previously been available.

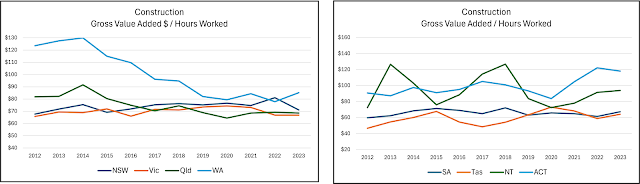

The hours worked data starts in 2011-12, and the state industry GVA data is up to 2022-23, so this post covers the period 2011-12 to 2022-23. As Figure 1 shows, over that period there has been great variation between the states and territories in both their level and their trends in GVA per hour worked, which makes comparisons difficult. Therefore the post is in two sections.

Figure 1. State and territory construction productivity 2012-2023

Sources: ABS 6150, ABS 5220 [1].

The first section of the post compares GVA per hour worked over the five years 2018-19 to 2022-23, looking at similarities and differences between the states and territories. The average of the quarterly shares of building and engineering work in total construction work done in each state and territory between 2018-19 and 2022-23 is also shown. All annual data is for the year ended in June.

The second section is on long-run trends in each state and territory between 2011-12 and 2022-23. This has the GVA per hour worked and average shares of work done data, plus the volume of work done to show the relationship between changes in work done and GVA per hour worked. Because of the great variation between the states and territories in GVA per hour worked, section two is organised as four sets of pairs: New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria; Queensland and Western Australia (WA); South Australia (SA) and Tasmania; and the Northern Territory (NT) and Australian Capital Territory (ACT).

This analysis of trends and performance of GVA per hour worked looks at three factors: the effect of the mining boom and the average of the quarterly shares of building and engineering work in total construction work done; the effect of changes in the volume of work done; and the effect of the small size of the industry in Tasmania and the two territories.

States and Territories Construction Productivity 2019-2023

In 2023 four states had a similar level of around $70 GVA per hour worked: NSW, Victoria, Queensland and SA. Tasmania was closer to $65, and WA $85. However, the NT and ACT were highest with $94 and $118 respectively, and both the territories also had higher levels of GVA per hour worked than the states in 2022.

As Figure 2 shows, GVA per hour worked in NSW and Victoria in 2023 is lower than 2019, and was the same in Queensland and Tasmania. In NT, ACT, WA and SA the level in 2023 is higher than the pre-pandemic level in 2019. Since 2019 WA had a higher level in all years than the other states except for NSW in 2022, although in 2020 the difference was only $2.

Figure 2. State and territory construction productivity 2019-2023

Sources: ABS 6150, ABS 5220.

Clearly there is no common level of construction GVA per hour worked across the states and territories. Construction productivity varies from year to year both within and between them. Since 2019 productivity in the two territories has been higher and in SA and Tasmania, the two smallest states, lower than the largest states of NSW and Victoria. Queensland is close to SA and WA is close to the NT.

One potential explanation for differences between the states and territories is the composition of output, the difference in the shares of building and engineering work in total construction work done, because there is evidence engineering work has higher productivity than building work due to larger projects with more heavy machinery and equipment used [3]. As Figure 3 shows this could apply to WA and the NT, which both have had a larger share of engineering since 2019 and higher productivity than other states.

Figure 3. Shares of building and engineering work

Source: ABS 8755. Quarterly chain volume measures [3].

For other states the picture is mixed. The share of engineering in Queensland, SA and Tasmania was higher than in NSW and Victoria, but their productivity was lower. The ACT had the lowest share of engineering but the highest productivity. Unfortunately, differences between the states and territories in the share of engineering in construction work done cannot satisfactorily account for differences in GVA per hour worked since 2019, with the possible exceptions of WA and NT.

States and Territories Construction Productivity 2012-2023

The figures below show each state with their GVA per hour worked and value of construction work done (in inflation adjusted chain volume measures, so referred to here as volume). This also allows comparison of the size of the industry between states.

NSW and Victoria

The level of GVA per hour worked in NSW and Victoria is very similar and for both has fluctuated around $70 since 2012. Until 2021 it was usually pro-cyclical, increasing as the volume of work done increased, but there were exceptions like NSW in 2018 when work done fell but GVA per hour increased and Victoria in 2016 when the volume of work done increased but GVA per hour fell. Then in 2022 in both states work done increased but GVA per hour worked fell.

Figure 4. Gross value added per hour worked and construction work done

Sources: ABS 5220, ABS 6150, ABS 8755.

These states have the largest amount of construction work. The volume measures of work done in 2023 were around $80 billion for NSW and $70 billion for Victoria. The size of their markets means they are diversified across all types of work, and less affected by individual major projects. The states’ average shares of building and engineering were almost the same in the two periods 2012-18 and 2019-23, with higher GVA per hour worked and a higher share of engineering in NSW since 2012, an effect that became more noticeable after 2019. In 2023 the volume of work had risen to record highs in both states.

After recent increases in regulatory requirements introduced to address building quality and safety issues, the high share of building work in these states may have required more people working on compliance. Although many might be working offsite, an increase in the number of people employed will have affected the industry’s productivity level. The high share of building work might also have given the CFMEU a significant role in these states, which may have affected their onsite productivity. Both these factors will apply to some extent to other states and territories as well.

Figure 5. Shares of building and engineering work

Source: ABS 8755.

Queensland and Western Australia

In 2014 the Australian mining boom peaked with the value of work done in these states reaching $80 billion in Queensland, mainly due to construction of LNG plants, and $70 billion in WA, mainly due to construction of new mines. The pro-cyclical nature of construction productivity is clearly seen in these states, GVA per hour worked followed the fall in the volume of work, which fell to around half the peak level, with GVA per hour worked declining by around 30 percent in Queensland and 20 percent in WA [4].

Figure 6. Gross value added per hour worked and construction work done

Sources: ABS 5220, ABS 6150, ABS 8755.

Although all states were affected by the mining boom, these two are the most resource intensive and were impacted the most. The Queensland economy is larger and more diversified compared to WA, which is why the volume of construction since 2016 has been greater there. The high share of engineering construction at 60-70 percent in WA accounts for the very high level of GVA per hour worked there.

Figure 7. Shares of building and engineering work

Source: ABS 8755.

South Australia and Tasmania

The volume of work done in these states is much lower than elsewhere. In 2023 it was nearly $16 billion in SA, where GVA per hour worked was similar to Victoria, and about $4 billion in Tasmania, where GVA per hour worked is lower and shows the big rises and falls associated with large projects commencing and completing in small markets.

Although their GVA per hour worked is lower than NSW and Victoria, these states have had higher shares of engineering in their averages of work done. The small market effects probably outweigh the higher share of engineering in their level of GVA per hour worked.

Figure 8. Gross value added per hour worked and construction work done

Sources: ABS 5220, ABS 6150, ABS 8755.

Figure 9. Shares of building and engineering work

Source: ABS 8755.

Northern Territory and ACT

The territories have distinctive characteristics. Both are very small markets, in 2023 the NT had about $3.2 billion work done and the ACT $3.9 billion work done. During the mining boom work done in the NT rose to over $11 billion in 2015, although some of the work will have been on defence projects, but GVA per hour worked did not peak until 2018. In the ACT GVA per hour worked took off in 2020 and increased by 50 percent, while the value of work done has been the same.

Figure 10. Gross value added per hour worked and construction work done

Sources: ABS 5220, ABS 6150, ABS 8755.

The NT and ACT are at opposite extremes for shares in construction work done. The NT has the highest share of engineering work at around 70 percent of the total, similar to WA in 2012-18 but slightly higher in 2029-23, and the lowest share of building work. The level of GVA per hour worked is also similar to WA, and their similar levels of GVA per hour worked and share of engineering gives some support to the idea that engineering has higher productivity than building.

However, the ACT complicates the picture, because the level of GVA per hour worked is higher but the ACT has the highest percent share of building work at nearly 80 percent of the total, and the lowest share of engineering work.

Figure 11. Shares of building and engineering work

Source: ABS 8755.

Conclusion

The ratio of hours worked to industry gross value added (GVA) is a measure of labour productivity. Using ABS data the level of construction GVA per hour worked for Australian state and territories can be found and compared from 2011-12, when the hours worked data starts, to 2022-23, when the state industry GVA data ends. In 2023 NSW, Victoria, Queensland and SA had a similar level of around $70 GVA per hour worked, Tasmania was closer to $65, and WA $85. The NT and ACT were higher with $94 and $118.

This comparison of state and territory trends and levels of GVA per hour worked looked at three factors: the effect of the mining boom and the average share of engineering in construction work done; the effect of changes in the amount of work done; and the effect of the small size of the industry in Tasmania and the two territories.

The share of engineering work is very high in WA and the NT, and in Queensland up to 2018. During the mining boom the volume of construction work done there reached record levels between 2011 and 2014, before falling in Queensland and WA by around half to more typical levels from 2018. In WA work done fell by two thirds between 2015 and 2023. GVA per hour worked went up and down as it followed the rise and fall in the volume of work done, showing a strong pro-cyclical relationship between changes in their level of productivity and changes in the amount of work done. In Australia, the level of both GVA per hour worked and share of engineering is highest in WA and NT.

The relationship between GVA per hour worked, the share of engineering, and the volume of work done is not as clear in the other states and the ACT. In NSW and Victoria the volume of work done has increased over the last few years but GVA per hour worked has fallen. In SA and Tasmania, the volume of work done has increased over the last few years but GVA per hour worked has not, while in the ACT GVA per hour worked has increased but the volume of work done has not.

The volume of work done varies greatly, with big states having larger and more diversified construction markets. In 2023 the volume of work done in NSW was almost $80 billion, nearly $70 billion in Victoria, and in Queensland almost $50 billion It was close to $40 billion in WA and $9 billion in SA. However, in the territories and Tasmania, the volume of work done is small, typically only $3 to $4 billion a year, and GVA per hour worked in these small markets increased and decreased by large amounts. This is probably due to the effect of large projects commencing and completing, and is particularly noticeable in the NT.

These differences between the States and territories shows that productivity is affected by local factors such as the size of the market and diversification of work, particularly in the small states of SA and Tasmania, and the NT and the ACT. This might have two effects. The first is in the territories, where the commencement of large projects appears to lead to big changes in work done and a more volatile pattern in productivity. Compared to NSW and Victoria the territories have much more variation over time with big changes in the level of GVA per hour worked. The second effect might be seen in SA and Tasmania, where a factor in their lower level of GVA per hour worked compared to NSW and Victoria could be a less diversified market and more small firms.

Finally, is there a more misused and misunderstood concept than construction productivity? Misused because it is often linked to growth, but as a ratio of inputs to output, it does not measure growth in industry output. Misunderstood because it is assumed that no increase in labour productivity is ‘bad’ or ‘poor’ and means the industry is not developing capability or advancing in technology.

In fact, the lack of growth in construction productivity probably indicates a high level of efficiency in an industry that has been refining it’s system of production using industrialised materials like steel, concrete and glass since the nineteenth century, and traditional materials like brick and timber for millennia. Once an industry is at or close to the efficiency frontier there is not much room for productivity growth [5].

Also, although the ratio of labour input to output has not decreased, which leads to higher productivity, there has been recent shift in employment from onsite to offsite with an increase in the number of people employed in designing, planning and managing construction projects. Some unknown proportion of these people will be working on BIM and other digital systems, as these technologies become more widely used and more firms become digitised. There will also be more people working on compliance due to recent increases in regulatory requirements introduced to address building quality and safety issues.

Labour productivity is typically pro-cyclical and moves up and down with the building cycle and activity levels. Unlike other targets such as business investment, R&D or skills and training, the long-term nature of productivity means it is not suitable as a policy target.

*

[1] ABS 6150 Modelled state and territory jobs and hours worked estimates by industry. Quarterly data annualised to June.

ABS 5220 State Accounts – Industry Gross Value Added for Construction, chain volume measures (the value of output minus the value of intermediate consumption adjusted for price changes).

GVA per hour worked is industry GVA divided by the annual total of hours worked:

Hours million Industry GVA GVA per hour

2023 Annual total $ billion worked $

NSW 694.4 49,399 71

[2] Their different levels of labour productivity were analysed in a 2022 post on Construction Productivity Trends for Building, Engineering and Construction Services using GVA per person employed.

[3] ABS 8755 Construction Work Done, States and Territories, chain volume measures. The quarterly shares of building and engineering in total work done are averaged over the time period used.

[4] The effect of the mining boom was discussed in a 2023 post on The Long Cycle in Australian Construction Productivity using GVA per person employed.

[5] This argument was made in a 2023 post Is Productivity Growth in Construction Possible?

Subscribe on Substack here

https://gerarddevalence.substack.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comment and for reading the blog. I hope you find it interesting and useful. If you would like to subscribe the best way is through Substack here:

https://gerarddevalence.substack.com

Thank you

Gerard